Your average film-goer, I suspect, thinks of a movie as what their older name was – moving pictures. You go into a film anticipating seeing a series of sequential images (along with sound, of course) that tells you a connected narrative. The means by which this story is told may involve a few techniques and tricks that we have become aware of through discussions of film technique – close-ups, tracking shots, fast cuts, and so on. The modern viewer is more sophisticated that the first film-goers, who ducked out of the way when a train seemed to be pulling into a station almost head-on, or who thought Winsor McKay’s animated Gertie the Dinosaur was a mechanical contraption.

Still, there are plenty of technical details to shooting, choices made in the way something is filmed, or tricks of the trade which don’t notice unless they are spectacular, or they are much commented on. So audiences are aware of Alfred Hitchcock’s use of elaborate camera moves, or his use of almost continuous filming with very few cuts in Rope. But they don’t know about subtler things, like a director’s using particular colors to set a mood or to indicate a character’s importance. They don’t notice his use of placing subjects consistently in the front or middle or background to indicate significance or some other aspect. Whether the subject of a shot is centrally located might have great importance. They might notice the use of a special effect, but not know the reason for its presence. Directors rely upon such tricks to enhance the viewing experience by undetectably (one might say “subliminally”, but that word is overused and often improperly used) affecting the viewer’s mood and emotions. Sometimes it’s not so subtle, but it’s still there, an unusual effect that throws out usual expectations off-balance.

Whether subtle or blatant, using unexpected techniques can certainly affect the viewing experience. There is no reason that the film should only consist of images simply depicting the scene directly. For a blatant example, consider the movie Angry Red Planet (195 ). It tells the story of the first Martian expedition in the usual science fiction images. But trailers for the film refused to show the scenes taking place on Mars, and teased the audience with the wonders of “Cinemagic”, a new screen process that would produce images unlike any they had seen before, and would only show images NOT in Cinemagic in the trailer.

Cinemagic isn’t properly explained on any of the internet sites I’ve seen. It appears to be a deliberate effort to produce a heavily Solarized image, then tinting it red. All scenes taking place on the Martian surface (outside the space ship, anyway) are shot this way. It certainly does produce an eerie effect, a “we’re not in Kansas anymore, Toto”, in which the Brave New World isn’t in color, but in red with glowing shadows.

It’s been said that the process was the result of a mistake, and that it was used to cover up the poor quality of the effects work. But that cannot be the whole story – it appears as if the effects and shots were planned with this effect explicitly in mind. It certainly does affect the way you experience the scenes on Mars. There’s not really any good or scientific reason for things to appear in this Solarization-through-a-red-filter way on Mars. But it certainly works in putting you in a very different place. You don’t feel that these characters are simply walking around in a desert locale on Earth, as with the films Robinson Crusoe on Mars or the more recent The Martian.

What does this have to do with vampires?

Vampires, possibly because of their association with mirrors or their later trait of dissolving in sunlight, have been depicted in films that tend to use such tricks and effects, far more than any other type of monster. You don’t see these shenanigans with the Frankenstein monster, or the werewolves, the resurrected mummies or fishmen, invisible men or Mr. Hyde. But directors have gone out of their way, using obvious and noinobvious tricks, to give vampire films a distorted reality not granted any other type of monster.

Let’s start with the oldest existing film version of Dracula. In Murnau’s 1922 Nosferatu, the hero Hutter feels (according to the intertitle) that he has entered a strange region when he crosses a bridge to Count Orlok’s. He is greeted by a strange black coach, with the coachman garbed in black, and the horses covered in black cloth, as well:

As they drive on, the coach takes on an eerie appearance:

The forest is ablaze in white light, and odd black smoke billows in the lower left corner. It looks wrong, somehow.

What Murnau did was to print this portion of the film as a negative, reversing black for white, and vice-versa. We can easily re-invert this on the computer, restoring the original look of the shot:

The scene looks perfectly normal. Instead of an oddly glowing forest, we have a forest in shadow. The black smoke is really white smoke in the lower left. In order to make the coach, driver, and horses appear to be black when reversed in a negative, it is a white coach, and the garments are white.

The entire coach ride sequence takes only a minute and a half, and the “negative” portion only 15 seconds out of that. That’s a lot of work for so short a shot, which required painting or replacing the coach, as well as all the clothes. But Murnau clearly felt it was worth it to establish the out-of-kilter mood.

Shortly after, Hutter walks to the castle, where gates open apparently of their own agency, with no one to operate them. This happens throughout the castle scenes, and it’s now a cliché, but it was a new innovation at the time, and contributes to the otherworldliness of the scenes.

Hutter meets Orlok, standing outside, and in apparent daylight

Why doesn’t the vampire melt in the sunlight? The most likely answer is that this scene, as well as those before it, were supposed to be printed on color stock, probably dark blue. It was a common practice to use colored stock to create a mood. A common and obvious practice was the use of red stock when a fire was taking place (as in the scenes with an erupting volcano in The Lost World, or the Fire caverns in The Thief of Bagdad). Night scenes were usually tinted blue, and the coach journey and this meeting outside the castle might be expected to be so tinted. Indeed, David J. Skal, in his authoritative book on the history of Dracula onscreen, Hollywood Gothic, says that the notes for the restoration of Nosferatu call for the use of tinted stock (although no restoration thus far seems to have actually used it.)

But there is another, subtler possibility. It could be that these are meant to be scenes taking place at night, but which are shown as if in daylight, not to save the costs of tinting, but to add another layer of unreality. This might seem rather far-fetched, but we’ll see a more obvious case of this when we get to Dreyer’s film Vampyr. In any event, we know it is night, because the intertitles have Count Orlok saying that it is midnight, and the servants are asleep.

Several odd things occur to reinforce the weird, dream-like nature of the story – Orlok reads from a sheet covered not with ordinary writing, but with cabalistic symbols. Hutter’s wife, Ellen, seems to feel a bond with Orlok, and goes sleepwalking. Orlok comes in to Hutter’s room through a self-opening door in the night, lit by a preternatural light. But the next directorial trick of the sort I’m highlighting occurs when Orlok loads his coffins filled with earth by himself, with no help (as he has in the novel). His actions are speeded-up by adjusting the speed of the film while recording. When the final coffin is in place, Orlok simply lies down in it and the lid fastens itself, though the wonder of stop-motion photography. To an audience still unfamiliar with such tricks, it would have been far more effective and far stranger than we see it today.

Later, aboard the ship there are some explicit and startling effects – Orlok’s coffin opens by itself, and the Count’s body rises upright without his assistance, rising as if tilted up on a Board. This is clearly strange and nightmarish, although not all that subtle. A less explicit image is of the canvas covering on the hatch moving aside by itself (more stop-motion) and the hatch raising itself.

The scenes of Knock (the Renfield character) in his cell shouting that “The Master is Here!”, then settling down to an unnatural and still calm look odd. I think that they may have been filmed in reverse, then printed so that the motions , performed in reverse, appear to run in the opposite order.

Finally, there is the ending, where Ellen Hutter sacrifices herself and so delaying Orlok’s departure so that the sunlight catches him, and he dissolves in sunlight. Orlok turns transparent, and disappears in a puff of smoke

Add to these the many shots where Orlok’s shadow looms large and threatening over people, or climbing the stairs, or opening a door, and you have a combination of very explicit dream-images and subtler, practically or completely un-noticed images re-inforcing the dream-nature of the story told. This is completely unlike, say, the 1910 Edison Frankenstein or the 1925 Lost World.

The next adaptation of Stoker’s novel to film was the 1931 Universal film Dracula, the one based on the Broadway play Dracula, which in turn was based on the British play written by Hamilton Deane for his company. All of these versions had the blessing of Florence Stoker, who had worked to have the un-certified Nosferatu (for which she received no royalties) suppressed. The play is more faithful to the novel, but necessarily makes condensations, changes, and cuts in order to fit the expansive, coincidence-heavy, multiple location, and too-many-character story to the stage. John Balderston considerably rewrote it for the Broadway stage. It was subsequently rewritten and expanded for the screen, partly by Balderston and also by Garrett Fort (who gets sole screen credit).

First, a word about that stage play. It was something of a spectacular, with lots of showy effects and stage magic. Bats fly around onstage, using a variety of methods and clever effects that make them appear to fly impossibly through places where no controlling wires can go. Dracula disappears onstage, courtesy of a trapdoor and a wire-stiffened cape with a high collar. At the ends, Dracula is clearly and undoubtedly destroyed by having a stake driven through his heart as he lies in his coffin. (All these effects were repeated when the play was revived in 1979). Although these indicated something out of the ordinary, you couldn’t exactly call it “dreamlike” But there was no ambiguity here — clearly something supernatural and out of the ordinary was occurring, and it made for a spectacular evening at the theater.

Little of this made the transition to the screen. Everything was toned down in the service of being more serious and to avoid offending the sensibilities of movie audiences. Dracula dies from having a stake driven into his heart – but it occurs discreetly offscreen, not in a showy special effect. (His victim, Lucy Weston – her name chopped down from the novel’s “Lucy Westenra” for ease in remembering – isn’t even mentioned as being staked. She’s conveniently forgotten, although the simultaneously made Spanish version does have her staking spoken of, at least) Dracula doesn’t disappear onscreen, and he doesn’t turn into a bat onscreen (Universal eventually did show that transformation onscreen, but not for another decade and a half.).

A lot of the time you got the impression that they forget this was a movie, and not merely a filmed stage play. The camera rarely moves around, but stays fixed in place. Renfield , the insane patient of Dr. Seward, seems to have free run of the house, and keeps popping up. That made sense onstage, where you couldn’t easily change locales, but is absurd in a movie, where you can cut to a scene of his cell. When Dracula changes into a wolf and runs across the lawn, we know this happens because one of the characters says that he sees the wolf (just as in the stage play), instead of the movie actually showing the wolf running.

This wouldn’t seem to be a very likely atmosphere for dreamlike, reality-questioning images. Surprisingly, there are some of these, and they all occur in the initial portion of the film, featuring Renfield’s visit to Dracula’s castle in Transylvania – something notably not depicted in the stage play. ( In the novel, of course, it is Harker who goes to Transylvania. Renfield is merely an inmate in Seward’s asylum who seems sensitive to Dracula’s mental powers. Nevertheless, filmmakers generally try to make Renfield’s connection more definite, so the Universal film replaces Harker as the real estate agent with Renfield, who goes insane on the return trip to England. Similarly, in Nosferatu Knock, the Renfield character is Hutter/Harker’s boss. )

The weird atmosphere starts with Dracula and his brides emerging from their coffins in a scene unaccompanied by a score – which adds to its oddness. There are no words, either, nor do the characters make eye contact. It’s notable that director Tod Browning (and cinematographer Karl Freund, who reportedly shared directoral duties) never actually show anyone emerging from a coffin. We see the coffin lid creak open and a hand slowly and writhingly emerge. But then the camera cuts away, and we do not see it open, nor the vampire lying within. Instead, we only return to the vampire when he or she is standing beside the coffin.

Accompanying this is a shot that is not rationally needed, and makes no real sense – it shows a wasp emerging from its own miniature coffin, like an insect vampire. It conveys, perhaps, an idea of the weird nature of the vampire. It makes no sense for this to be in the vaults of Castle Dracula, but it does set a mood.

The next thing sort of breaks the mood for modern audiences – we see armadillos wandering the castle. Armadillos? In Transylvania? But in 1931, most audiences – away from Texas and the southeast, at least – probably wouldn’t recognize the armadillos for what they were. Strangely-shaped and oversized rats, the audience probably thought. More dream-state stuff. Dracula and his wives slowly mount the steps to leave the vault, moving slowly and unnaturally.

Dracula, in disguise, picks up Renfield at Borgo Pass, but there’s no sort of reality-inverting trick using negative images here. During the trip, Renfield looks out of his carriage to see no driver, but a bat flying over the horses, and apparently guiding them. When they reach the castle, he gets out and the driver has vanished. He goes alone into the hall, and is greeted by Dracula at the top of a long set of steps in the Grand Hall of the castle, which is in ruins and appears abandoned. There is an enormous spider web woven across the staircase, which the Count apparently walks through, coming down, and then going back up. How this is done is not shown – the camera cuts away as he approaches it – but Renfield is forced to tear an opening in it with his walking stick.

We see the spider which wove this web – an amateurish model, which Dracula remarks upon, the creature seeking its natural prey, the fly “The blood is the life” says Dracula, a line given to Renfield in the novel (The symbolism is clear and rather heavy-handed – Dracula is the spider and others, including Renfield, his victims. The advertising even emphasized this aspect, showing the web in posters for the film)

The existence of this huge oversized web, its oversized spider, and Dracula’s abilities to pass through it all fit the nature of rationally absurd to mood-setting items that this essay points out. It’s also about the last one in the film. After this, things get rather pedestrian. Dracula’s wives are demure and sort of boring. At least in the Spanish version, they appear unusual and predatory.

Only a year later, Carl Dreyer presented his image of vampires in the film Vampyr, which is about as far away from the rationalized Hollywood image of vampires as one can get. As with Nosferatu, we are here presented with a film that not merely has dreamlike images and touches, but virtually all of the film is intended to be a dreamlike experience. Actions and statements frequently make no logical sense, and the film seeks more to create a mood than to tell a coherent story. The titles tell that the film was inspired by Sheridan le Fanu’s book Through a Glass Darkly, which contains the vampire novella Carmilla. This has often been interpreted as the film being an adaptation of Carmilla, which it clearly is not. It’s frequently hard to tell what the film’s story is supposed to be. It appears to have been filmed poorly in one language, with subtitles/intertitles in another, neither of which is English. In fact, the film is a German-French production by a Danish director. The original intertitles (although this is not a silent film) were in German. The first English-language editions were badly reproduced, badly edited, and badly translated. The recent DVD re-issue by Criterion corrects many of the problems, but the film still is not pristine – deliberately.

It tells the story of Allan Grey, played by Julian West, the main backer of the film. With his long face and lantern jaw he looks surprisingly like horror author H. P. Lovecraft, but that is purely coincidental – in 1932 Lovecraft wasn’t well-known, and not many people knew what he looked like.. There is a female vampire in the film, but she is completely unlike le Fanu’s apparently young vampire, and unlike any other leads female vampire in any other movie – she is neither sexy nor sophisticated, utterly without any attraction. She appears to be an older woman, and she contrives at the death of one character and seeks the blood of others.

Without going into the plot, what is of interest here are the many images that make no coherent sense, but set a dreamlike sense of strangeness. Shadows move independently of the persons apparently casting them. In one scene, shadows walk across a lawn with no one casting them. In another sequence Allan Grey turns transparent, a sign that he is dreaming. In the dream, he is in a coffin with a window over his face, allowing him to see people (including the vampire) preparing him for burial.

Vampyr (1932) — Shadows in the water apparently cast by no one

Vampyr (1932) — The hero turns transparent as he dreams

Vampyr (1932) — Shadow moves independent of the person throwing it

At the beginning, Allan uses a candle to light things in his room and see them more clearly – even though it is still broad daylight! At the end, one character looks for the grave of the vampire in order to drive a stake through her heart and destroy her. He uses a lantern to read the tombstone – even though it is again broad daylight. With Allan’s help, they open the tomb and drive a metal stake into her heart. The body does not dissolve.

Vampyr (1932) — Hero using Lantern in Broad Daylight

Vampyr (1932) — The vampire in her coffin in daylight

What’s interesting is that the vampire does not dissolve in daylight. This was after Nosferatu but before the resurrection of the notion of sunlight dissolving vampires re-introduced by Return of the Vampire, Son of Dracula, and House of Frankenstein, so I took it as further evidence that the notion of daylight destroying vampires had not taken hold in the popular mind. But, on the other hand, is it possible that they brightly-lit scene is, in fact, not in daylight? After all, they needed to use a lantern to read the tombstone. It’s not a question of whether the scene should be tinted dark blue or not – Director Carl Dreyer was not using such effects, and was seeking an ambiguous, unreal state for his film.

Hollywood vampire films in the 1940s and 1950s tended to be more “rational”, with less mysticism and less desire to create an unreal aura. The films House of Frankenstein and House of Dracula even tried to rationalize the monsters. Science fiction seemed to adopt vampires, with films like Atom Age Vampire and The Last Man on Earth (adapted from Richard Matheson’s scientific vampire novel, I Am Legend) – there wasn’t room for those early dreamy creatures.

But creative filming started to creep back in. In the fourth of Hammer’s Dracula films, Dracula has Risen from the Grave, Dracula is seen reflected in a pool of water, something that pop culture since Stoker has declared impossible, although the Hammer series apparently never weighed in on this aspect of vampires. It’s arguably too good an image to pass up. Certainly the image itself is ethereal and dreamlike – we never see Dracula’s image clearly, in undisturbed water. Later in the film, we clearly see a reflection of Dracula in a window. His is likely an oversight – it could easily have been corrected by restaging the shot, or removing the reflecting panes. But it’s also possible that in this universe, vampires do reflect.

One further aspect of the film deserves mention – according to the Wikipedia article on it “Whenever Dracula (or his castle) is in a scene, the frame edges are tinged crimson, amber and yellow.” I have looked for this effect, but don’t see it. In any event, it is another of those almost-subliminal photographic details that was used to set up a mood, unknown to the audience.

Two versions of Dracula appeared in the next few years that tried to be more faithful to Stoker’s novel. Jess Franco’s 1970 Count Dracula is surprisingly good and faithful in the first half, but loses steam halfway through. It doesn’t noticeably try to produce a dreamlike mood. The second version, though, the PBS/BBC 1977 version , restores an image from the novel not previously seen onscreen, which by itself perfectly brings the unreal nature of the story to the fore – Dracula crawling facefirst down the wall of his castle, watched by Harker.

Louis Jordan as Dracula crawls face-first down the castle wall in the 1976 BBC adaptation — the first I’m aware of where he does so. On the right is a 19th century illustration of the same scene.

The TV production also features a dreamlike segment using high-contrast monocolor video that resembles the solarization in Nosferatu.

Dracula (1976) — High-contrast scene resembles solarization in Nosferatu. Adds an element of unreality to the production.

The 1979 John Badham film derived from the revival of the Balderston/Deane play starring Frank Langella is mostly as straightforward as its 1931 predecessor, but does feature two notable scenes that plunge us into the dream state. One is the reflection of “Mina” (actually, the character of Lucy in all other versions, here further re-imaging as Van Helsing’s daughter), who is reflected in a puddle of water. The lines about the vampire not being visible in a mirror (and the scenes at either Castle Dracula or at Dr. Seward’s that inspire them) are noticeably absent from this film, so it’s possible that it takes the stance that vampire are visible in mirrors. But the scene is exactly like the one in Dracula has Risen from the Grave – the character is never seen clearly or distinctly, in still water. Only in moving water, giving it an unreal aspect. I suspect Badham saw Freddie Francis’ film and took this startling image from it. He also added pinpoints of light to “Mina”s eyes, further removing it from reality.

The film also features a very unreal scene of the seduction of “Lucy” by Dracula, filmed by Maurice Binder, best known for his surreal opening title sequences for the James Bond movies. We see the silhouettes of Langella as Dracula and Kate Nelligan as Lucy, filmed with red lasers playing through a special effects fog. It’s also turned sideways, so the standing figures appear suspended horizontally. It’s hard to describe this as other than dreamlike. It’s completely unlike the rest of the film.

Also released the same year was Werner Herzog’s remake of Nosferatu. Although it duplicated the storyline and the makeup from the original, it avoided the sorts of visual tricks used there. It did feature slow-motion photography of bats in flight, and opens with scenes of the Guanajato mummies of Mexico, giving an eerie atmosphere, but otherwise the film doesn’t strive for the same air of unreality as its predecessor. The same year the horror spoof Love at First Bite featured George Hamilton as Dracula and Arte Johnson as Renfield, but the film played for laughs, of course, and made no efforts to establish an unreal atmosphere.

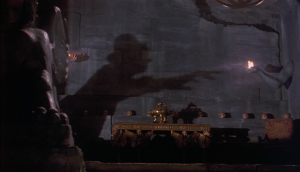

When Francis Ford Coppola set out to make his film Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), he avoided much of the new CGI technology, and reached back to earlier films for his inspiration. He very clearly mined Vampyr and other films for his mood-setting imagery, at the same time putting more of the novel onto the screen than any other director before him. He has the dissociated shadows from Vampyr, used several times as Dracula’s shadows appear to move completely independently of him.

His eye appears in the background as Harker’s train approaches Transylvania.

Dracula does not appear in Harker’s shaving mirror (as in the novel). He appears to move with using his feet, gliding over the floor. When he arises from his coffin, he pivots upright as if raised on a board, as in the original Nosferatu. When Dracula, in the guise of the coachman, reaches for Harker to draw him into the coach, his arm stretches out preternaturally long.

The coach travels to the castle (which resembles an industrial-era factory in the shape of a sitting man, more than a medieval castle) he is perilously close to the edge. He sees the fires of Walpurgisnacht, described in Stoker’s novel (and another eerie, dream-state image) but never before depicted on film.

When Harker wanders the Castle by himself, he encounters liquids that drip upwards in defiance of gravity (and misses seeing rodents running on the undersides of beams, also defying gravity). He encounters Dracula’s brides, with them appearing suddenly under the covers or rising through the bed. Upon Dracula’s appearance, they retreat, using film run backwards, and with two women interlinked to form the body of one – all extremely unusual mood-setting images. Indeed, Harker suspects all this to be a dream. He sees Dracula crawling headfirst down the castle wall, as in the 1976 version.

Back in Whitby, Lucy’s encounters with Dracula are depicted as very dreamlike images, with a werewolf-like Dracula embracing her. Similar shots of a werewolf-like Dracula bedevil the ship Varna then at sea. Dracula as a wolf is shown as a speeded-up Point Of View shot running through the landscape. All of this is very far removed from the matter-of-fact filming of most versions of the tale.

When Lucy is finally staked, the sequence was clearly filmed in reverse, then run backwards. Nothing is inherently impossible as filmed, but, like the final scenes of Knock in Nosferatu, it doesn’t look right, and the resting Lucy in her coffin looks unnaturally still.

Overall, this film goes farther than any other in working to create the unreal mood, as well as in trying to capture as much of the original novel as possible. It doesn’t entirely succeed in that goal. As David Skal points out, the romantic image of Dracula is completely at odds with Stoker’s unsexy Darwinian superman. The entire prologue of the blaspheming Vlad becoming a vampire because of his loss of his wife (and his seeking her re-incarnation in Mina) is utterly alien to the book (see my essay Dracula’s Re-Incarnated Wife for a long look at this). But it’s undoubtedly not what Coppola or the public really wants – that Byronic , darkly sexual, seductive vampire is what really sells. Bela Lugosi, not really a sex symbol, used to get adoring letters from female fans making suggestions (the nature of which he wouldn’t reveal) in the wake of the 1931 film. It’s the equivalent of the women throwing panties at Tom Jones concerts.

Frankenstein came in for a similar re-vamping two years later with Coppola’s production of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Again, it was far more faithful overall than most of its predecessors, but still missed the mark of accurately translating the novel to the screen. Even so, it didn’t work at creating the same kinds of touches of unreality to create a dreamlike atmosphere as Coppola’s Dracula did. No Frankenstein film, does, in fact. Nor do Werewolf films, re-animated Mummy films, Invisible Man films, or those of any other monster. There is something about the vampire, and about Dracula in particular, that seems to call for this treatment. It is, to use the title of the George R. R. Martin 1982 novel about vampires, a Fevre Dream.