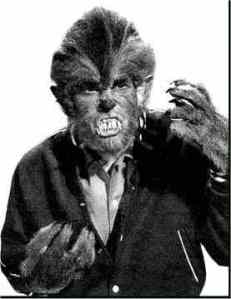

Lon Chaney Jr. As Larry Talbot, the Wolf Man

As a Boomer, I grew up in the cultural fallout of the 1940s — the cartoons I watched, many of the movies I saw on TV, much of the fiction I read (reprinted from the pulp magazine), and especially the fantastic horror films. Not long after I was born, Universal released to television its “Shock” package of horror films from the 1930s and 1940s.

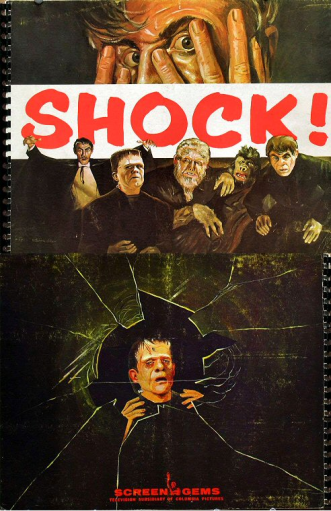

Front and Back cover of the Shock! movie package sent out to independent TV stations

They had run and rerun them to the theaters, but now television was taking over as the everyday medium, and they intended to squeeze some extra value out of those films by renting them out to independent television stations, which were desperate for inexpensive, slickly-produced material to fill their screens and bring in advertising revenue. In the wake of this came the monster fan magazines and the merchandising – monster plastic models from Aurora, Monster paint-by-number kits, monster trading cards and monster comics. The 1960s were the golden age of Monster Culture.

Of course, we watched the Universal movies over and over, absorbing all the details and learning the dialogue well enough to quote it. Frankenstein, Dracula, the Invisible Man, the Phantom of the Opera, the Mummy, Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde, and the Wolfman. They appeared in movies by themselves, then later in combinations, and finally with Abbott and Costello in comedies.

The Wolfman and the Mummy were odd ones, though, because, unlike the others, they had no classic literature behind them. The others were based on famous books, even The Phantom, with its pulp-novel origin in the work of Gaston Leroux, but there was no single literary work behind the Mummy and the Wolfman. I later learned that even the mummy could boast of some literary antecedents – Edgar Allen Poe, Arthur Conan Doyle, and even Dracula’s creator Bram Stoker wrote resurrected Mummy stories.

The Wolfman was different – although there really were legends of wolfmen and werewolves, there was no single work that stood behind the films, and none that cast the werewolf in quite the form he took in the films. In the legends, the werewolf was a consciously-invoked transformation, in which a human deliberately set about to become someone who could turn into a wolf. Hollywood changed that, blending the legend of the werewolf with the tradition of Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde to come up with a tragic figure, rather than an evil one – a good man who through no fault of his own would transform into a ravening monster every full moon. And the creature as depicted on the screen was not a wolf, but an odd hybrid of the two – a Wolf-Man, rather than a Werewolf. I didn’t realize quite how special this monster was until I carefully considered him, and realized that it was a far more complex thing than the movies portray at face value. Once I looked beneath the surface, I realized that there was much more there that I had absorbed as a kid. “Don’t pay attention to that ridiculous cover,” Vladimir Nabokov is supposed to have said in lectures about Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde. The real story wasn’t the hairy, ghoulish monster the movies showed, but the tragedy and the turmoil within. And so it is for his bastard child, the Wolfman, as well.

After the success of the Universal horror films Frankenstein, Dracula, and The Mummy, associate producer Robert Harris decided to try to mine another vein for horror. As he explained in a studio publicity article “One of the most prolific fields for motion picture stories has scarcely been scratched. This untapped field is found among the legends and folk tales of the people in the back countries of Europe. These stories have been handed down from generation to generation, stories so weird and bloodcurdling as to send cold chills along the spine…They are the greatest source for picture stories that exists today, only the film people seem to have passed them by.” (Quoted in Bryan Serms’ The Werewolf Filmography: 300+ Movies p. 238 (2017) )

Harris didn’t exactly pass the legends by, but he didn’t use them as he found them, either. Instead of a story about a man who becomes a wolf, the monster of the tale is an odd human-wolf hybrid. As Dr. Yogami (a scientist afflicted by the curse) puts it at one point: “A werewolf is neither man nor wolf, but a satanic creature with the worst qualities of both.” The afflicted acquires pointed ears, enlarge lower canines, pronounced hairiness on hands and face, and a wolfish disposition to attack and kill.

Nor is the werewolf one who seeks out the transformation, but one who has been wounded by another werewolf, just as a vampire can spread the contagion of vampirism by attacking another. Furthermore, the curse comes upon the sufferer on the night of the full moon, giving this Mr. Hyde-ish transformation the regularity of a timetable that the protagonist of Stevenson’s tale lacked.

Harris had thus come up with something new in the world. Our werewolves still are hairy man-wolves who can acquire the curse through an attack by another werewolf and change by the light of the full moon – all new things with this film – even though we ignore many of the other aspects lycanthropy as set out here. No other film features the curative power of the rare plant Mariphasa lupina lumina that blooms only by moonlight. Some pay lip-service to the idea that the werewolf must be slain by a loved one (as does John Landis’ later An American Werewolf in London), but ignore that rule when it becomes inconvenient.

As for the idea of a man-wolf hybrid and the source of that makeup, I think we have to look at how the movies are made and their limitations and strengths. Werewolves and Wolfmen were portrayed by people in heavy makeup from 1935 to 1981, and a bit beyond. Nowadays they’re often CGI creatures. Why?

For one thing, it’s hard to make a wolf or a dog seem large and threatening for more than a brief bit of film. You can get a few reaction shots of snarling canines, but not an entire movie of them. Moreover, it’s hard to get dogs and wolves to carry out extended and complex scripted motions. It’s too much trouble, and it probably won’t work. Even if it does, your audience is going to be amazed at the quality and training – but you want them to be scared and horrified.

You can make wolf puppets, manipulated by rods or by hands inside or even by stop-motion animation (all methods used in An American Werewolf in London and in The Howling, released at the same time), but it won’t be very convincing. Worse, it’s hard to portray human emotion. We want the audience to feel the pain and suffering of our transformed hero, not wonder at the effects.

So you make your monster a man with make-up. Above a;;, you must keep the center of the face relatively free of obstructions. A false nose and false teeth are acceptable, but an actor without his mouth and especially without his expressive eyes is in trouble. This is why our werewolves and wolfmen have those parts free. It’s why, decades later, the TV series Star Trek in all its manifestations featured aliens that were basically people, with makeup “appliances” added to the periphery of their faces, but with that emotive center left relatively intact.

The designer of the makeup was Jack Pierce, the legendary and eccentric Universal make-up man who created the Frankenstein Monster, the Bride of Frankenstein, and the Mummy. There is little doubt in my mind that he drew his inspiration from people afflicted with hypertrichosis, the congenital condition that made hair grow on their faces and hands. Adrian Jeftichew of Russia was so afflicted, and exhibited himself in French circuses. His son Fedor had the same condition, and appeared with his father, until he signed with Phineas Taylor Barnum in the United States. There his complex Russian name was reduced to a simpler form, and he became Jojo the Dog-Faced Boy. He died in 1904, but not before becoming a household name. (Decades later former Mouseketeer Annette Funicello had a novelty song hit with “Jojo the Dog-Faced Boy” in the 1960s)

Adrian Jeftichew with his son Fedor

Pierce came up with an extremely hairy makeup, the same one he would use years later for The Wolf Man, but star Henry Hull balked at wearing it. For years it was said that he didn’t want to be completely submerged in that overwhelming mass of hair, and spend hours in the makeup chair. But recently it has been pointed out that Hull had a reason for this – the script, at the end, calls for his wife to recognize him, even though he has been transformed into a werewolf. That couldn’t be believed if he was buried under a ton of makeup. Pierce didn’t relent, so Hull went over his head, and his objection was accepted by the producers. Pierce gave in, grudgingly, and produced his Werewolf Lite makeup, through which you can discern Hull’s features. But he wasn’t happy about it. Unlike the other productions Pierce was involved in, there were no publicity shots of Hull in the makeup chair being transformed into the Werewolf of London. Pierce refused to be photographed that way.

Henry Hull as The Werewolf of London

At the end of the film, Hull’s character is, indeed killed, and by a loved one. He is dispatched by a simple shot from a bullet – no silver involved. It’s a rather tragic story, ad one where you genuinely feel sorry for the titular monster. But it wasn’t a big box-office success. The Werewolf of London is an odd entry in the early 1930s Universal horror series. None of those involved in the other horror films of that time were involved – not directors Tod Browning or James Whale. Not the scriptwriters John Balderston and Garrett Fort. Not even the actors from the previous films. There had been talk of having Boris Karloff star in it, and of having Bela Lugosi as the werewolf who attacks him, but those castings did not occur. Instead we got the non-horror actors Henry Hull and Warner Oland. The only actor from prior horror was Valerie Hobson as Hull’s wife. She had just been Colin Clive’s wife in Bride of Frankenstein, where she replaced Mae Clarke from the 1931 original film as – well – the Bride of Frankenstein (the scientist). Maybe if they’d brought in some of the old crew Werewolf would have done better, and be better remembered.

Although most people don’t realize it, there was a Changing of the Guard at Universal in the late 1930s, and it profoundly affected the horror films. You can see the break in many ways. The earlier films were felt by their creators to be Classics, while the later ones were commercial fare. Karloff , after the third Frankenstein film, refused to appear as the monster, although he appeared in other roles, and appeared in publicity tours.

The mythology changed. In the first two Frankenstein films they were in Ingolstadt, and the laboratory was in a distant watchtower. In Son of Frankenstein, they are in the town of Frankenstein, and the laboratory is behind the house. The Mummy in the original film was Im-Ho-Tep, who appears as a normal, if slightly more wrinkled, human, and speaks and acts like a modern-day human. In the 1940s films the Mummy is Kharis, whose tongue has been torn out, and who remains wrapped in bandages. The early Dracula was Bela Lugosi. In the 1940s, he’s the yop-hatted and mustachioed John Carradine. The Invisible Man devolved from the 1930s literally mad scientist into a pedestrian secret agent in the 1940s.

So it’s not surprising that the Werewolf got transformed as well. It was as if The Werewolf of London hadn’t even existed. No notice of that film remained, and no reference was made to it. They took over many of the characteristics of the Werewolf for The Wolf Man, but they changed a lot, too. And it is with the 1940s incarnation of The Wolfman that this essay is really concerned.

The Wolf Man was the work of Curt Siodmak, a man who deserves to be better know, for all his pop-cultural influence. He wrote the script for the German film F.P. I Does not Answer a science-fiction/espionage film about a Floating Platform (the “FP1” of the title) that allowed transatlantic air travel in the days before planes had the fuel capacity and efficiency to cross the Atlantic. Years later he wrote a novel about Space Stations that took the concept to space. He also co-wrote the script for the science fiction film The Tunnel about a trans-Atlatic tunnel.

Fleeing the Nazis in the 1930s, he went to London and later to Hollywood, where he continued to write for the films. As I indicate in my essay on Vampires and Sunlight, he is one of the people responsible for reviving and popularizing the idea of vampires dissolving in sunlight. He is responsible for the first monster battle film (Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man) and for popularizing the notion of the Brain in the Aquarium with his best-selling novel Donovan’s Brain, which was filmed three times. He wrote the script for Earth vs. the Flying Saucers as well.

But it was his work on the Wolf Man for which he is best known, and which he considered his great achievement (The two different editions of his autobiography are entitled Wolf Man’s Maker and Even a Man Who is Pure in Heart). Siodmak took some of the elements from Harris’ script and story for Werewolf of London and revamped them. The idea of an involuntary and unwanted transformation into a monster after being attacked by another such afflicted monster is still there, as is the connection (after the first film, at least) with the full moon. But Siodmak invented much else. The Wolf Man gets the sign of the pentagram, and there is the poem that goes with the “legend”:

Even a Man who Goes to Church by Day

And says his prayers by Night

May become a Wolf when the wolfbane is in bloom

And the autumn moon is bright

From the poem, it seems as if another plant – the (very real) wolfbane, which had featured in Dracula, takes the place of Harris’ Himalayan Mariphasa lupina lumina as important to the curse, although it does not affect a temporary cure in this case.

The Wolf Man is particularly sensitive to silver, and may be killed by a silver bullet (or the head of a silver-tipped cane).

Even if you haven’t seen the film, you probably know the outline of the plot from seeing other 1940s Universal horror films, or from cultural references. Lawrence Talbot, played by Lon Chaney, Jr., born and raised in America, returns to his family’s ancestral home in England. There he is attacked by a gypsy who is a werewolf at night (played by Bela Lugosi, who finally did get to fulfill the role they wanted him to in the early 1930s). He finds that he turns into a werewolf himself at night, and begins to ravage the countryside and killing people. He is finally bludgeoned to death by his own father, Sir John Talbot, with the antique silver walking stick he purchased at the start of the film.

The Werewolf-lethal Silver-tipped cane

It seems like a simple and straightforward monster flick, but it’s not quite what it appears, as we will soon see.

First, though, I need to comment on the makeup. Jack Pierce had survived the Changing of the Guard at Universal, and was still doing the makeup in his eccentric and dictatorial way, and this time he wanted to execute the makeup the way he’d wanted to back in 1935. This time there was no script requirement that the Wolf Man be recognized while transformed. In fact, the idea is that he is unrecognizable.

A makeup very similar to Pierce’s original werewolf makeup had appeared in the 1932 Paramount film The Island of Lost Souls, based on H.G. Wells’ novel The Island of Dr. Moreau, in which the titular doctor works to transform animals into simulacra of human beings through surgery and (in an addition for the film) various rays. A lot of the makeup effects by Charles Gemora and Wally Westmore is genuinely disturbing. In particular, the makeup for the lupine Speaker of the Law (played, ironically, by Bela Lugosi) looks very much like Pierce’s Wolf Man makeup. Pierce must have burned to show his improved version of it.

Bela Lugosi as The Speaker of the Law in Island of Lost Souls

So his makeup for The Wolf Man pulled out all the stops. It’s artistically better, I think, than the Island of Lost Souls makeup, and more immersive than the makeup for The Werewolf of London.

Lon Chaney as The Wolf Man, and Chaney with Makeup Artist Jack Pierce

In this film we only see the transformation taking place on his legs and feet, which get hairier and hairier, but in subsequent Wolf Man films for Universal the transformation of his face is actually shown gradually taking place on camera.

Lon Chaney’s on-screen transformation from Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man

In this pre-CGI days this involved elaborate efforts, much mythologized and about which much that is not true has been written. Suffice it to say that the effect is extraordinary, and still holds up, even in these days of computerized effects. And all of it serves to hide the real intent of the scriptwriter. It’s hidden in plain view.

You see, in Siodmak’s script – not merely his original script, but the script even as filmed – it’s not clear that Lawrence Talbot ever really transforms into anything.

Throughout the film, whenever anyone asks if a man can actually transform into a wolf, it is met with hemming and hawing. They say that a man might think he’s transforming. “You ask me if a man can become a wolf,” says Sir John Talbot. “You mean can he take on the physical characteristics of an animal. No, that’s fantastic. However, I do believe that anything can happen to a man in his own mind. “

“Do you believe in werewolves?” asks the afflicted Larry Talbot.

“Why, I believe a man lost in the mazes of his own mind may imagine that he’s anything,” says Doctor Lloyd, who is treating him. “It’s probably an ancient explanation of the dual personality in each of us,“ says Sir John Talbot, referring to the werewolf legend This is repeated over and over, emphasizing that the transformation may only be taking place in Talbot’s mind.They also raise the possibility that mass hysteria may play a part, and that the beliefs of people around you can influence you. They even edge as far as suggesting that all this power of belief may cause some physical effect, the way stigmatics begin to manifest real wounds.

This is the way Siodmak wanted the film to be made – there would be no explicit shots of the Wolf Man, and certainly no footage of the actual transformation. It would all be offscreen – the attacks, the rustling in the bushes – all would imply but not actually show the Wolf Man, just as the scenes at the beginning do not show Bela Lugosi as a werewolf.

The only time you would see Talbot in his full Wolf Man glory would be at the end, when he’s being pursued by the scared and angry villagers. He would look into a pool of water in the moonlight, and see his face reflected as a monster. The effect would be rather like this magazine cover:

This is from Famous Fantastic Mysteries for October 1946, over five years after the film The Wolf Man. It’s by “Lawrence”, magazine illustrator Lawrence Sterne Stevens. As the title in the lower right indicates, this illustrates Wells’ Island of Dr. Moreau, which appeared complete in that issue

Why wasn’t it filmed that way? The studio clearly decided that the public would rather actually see the Wolf Man. In addition, they had that killer special effect where you could see the transformation on camera. (This lead to some odd results, all the same. As some critics have pointed out through the years, Talbot as The Wolf Man often isn’t wearing the clothes shown before and during the transformation. For that matter, Bela the Gypsy is shown without any clothes in his werewolf phase, but fully dressed – aside from shoes – when he reverts back to human.)

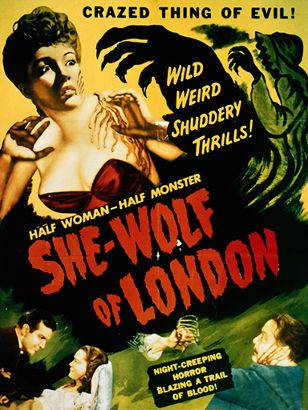

It’s a lot more pedestrian and a lot less artistic, but there can be little doubt that the studio did the right thing from a business point of view. Do you remember the 1946 film called She-Wolf of London?

It starred June Lockhart (Yes, that June Lockhart – Timmy’s Mom from Lassie and Maureen Robinson in Lost in Space, the quintessential 1960s TV Mom) as a woman who thinks she is turning into a werewolf. The werewolf is never seen, although its effects are. In the end, the werewolf transformation is revealed to be unreal, an attempt by other heirs to drive her character mad. What about Curucu, Beast of the Amazon from 1956?

Again, the titular beast is not seen until the end of the picture – only its effects. At the end, it is revealed to be a hoax.

This is what Curucu looked like at the end of the film

This film was actually scripted by Siodmak. It has never even been released to DVD. The point is, audiences want to see extraordinary things and effects. They want the fantasy. The sort of ambiguity and reality equivocation that feels like High Art is really Box Office Death.

So The Wolf Man ended up being a sort of compromise – it retained the dialogue as if it were about a man who might be transforming into a monster, but the actual film itself betrayed that concept, and delivered a very elaborate verification of that very transformation.

But there’s more. That very elaborate makeup and those painstaking transformation sequences hide a second secret of the film’s intent. One that continued with other Universal films featuring The Wolfman.

The Werewolf of London very explicitly recognized that Henry Hull’s character changed not into a wolf, but into a sort of hairy man-wolf hybrid. The dialogue acknowledges it, and the fact that he is recognizable underscores this. He is not said to transform into a Wolf, but into a Werewolf.

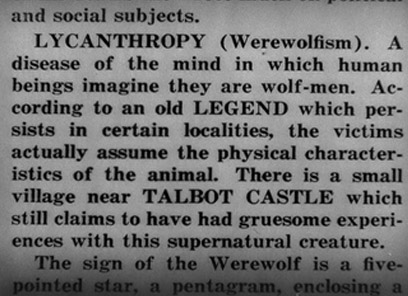

Not so with the Wolf Man. People repeatedly say that they saw a Wolf. Someone was attacked by a Wolf. They see the tracks of a Wolf. No one ever says that they saw a hairy man. The monster is never described in humanoid terms at all. Anyone who hasn’t heard about the Werewolf calls the thing simply a Wolf. When they have all those discussions about whether or not a real transformation took place, they talk about transforming into a Wolf, not a Wolf-Man or a Man-Wolf hybrid. The closest the come to suggesting a physical transformation into something not a wolf is in an introductory segment that looks like an afterthought. A set of hands (whose? We’re never told) goes to a set of bound volumes and pulls one out, flipping through the pages. The screen highlights an entry on Lycanthropy, saying that the person afflicted believes himself becoming a wolf-man, and may even acquire animal characteristics.

The poem quoted repeatedly throughout the film (twice in full, and with many references to parts of it) speaks of transformation into a Wolf, not a Wolf-Man. “You killed the Wolf” says Maleva the gypsy, who knows it was a werewolf. When Bela the gypsy transforms into a werewolf, he appears to be a real wolf, not a Wolf-Man, when he attacks, and is, in turn, killed by Talbot.

This looks like a major gaffe – you couldn’t mistake that hairy, upright, bipedal creature without wolf ears for a four-legged canine wolf. You’d never describe it in those terms. Yet this is the philosophy of the Universal movies involving the Wolf Man. There’s a sort of doublethink there – they depict a Wolf Man but the dialogue speaks of a Wolf, and everyone acts as if the creature really IS a wolf, not a Wolf-Man. It’s rather like the Japanese puppet theater bunraku performances, where the puppeteers are all dressed in black, and the audience convention is to act as if they’re invisible (and they would be, were they performing in front of a black background, as in the case of Black Light Theater ) But Bunraku performances almost invariably have detailed, well-lit backgrounds, in front of which the puppeteers are hopelessly visible. They are rescued by this convention. And so Universal horror films of the 1940s had a similar convention – show a Man-Wolf creature, but speak and act as if it’s really a wolf. In Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943), House of Frankenstein (1944), House of Dracula (1945), and in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948) people report seeing not a Wolf Man but a Wolf. In the last film, a mask of a wolf, with snout and large canine ears, is mistaken for the Wolf Man:

Left: The Wolf Mask as shown in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein

Right: The actual mask

Even in the title animation for Abbott and Costello meet Frankenstein, the Wolf Man is depicted as more of a Wolf than he seems in the actual film.

I’m not aware of any series carrying on this sort of doublethink, with the depiction of a human/wolf creature onscreen, but with the dialogue suggesting that it was a wolf. Humanoid werewolves started to populate films after Universal’s introducing the human/wolf hybrid, beginning (arguably) with Columbia’s Return of the Vampire in 1943.

Left: Werewolf from Return of the Vampire Right: I was a Teenage Werewolf

The 1957 American International film I was a Teenage Werewolf featured a humanoid werewolf (and was the biggest moneymaker for AIP, inspiring a host of uninspired imitations).The 1961 Hammer film Curse of the Werewolf, starring Oliver Reed, featured a humanoid werewolf (although with wolf-like ears, rather than human ones), despite the fact that the 1933 novel it is based on, Guy Endore’s The Werewolf of Paris, was about a man transforming himself into a wolf, not a wolf/human hybrid. (It was the only werewolf film made by Hammer, which made multiple films using other creatures that had been in the Universal pantheon).

Oliver Reed in Curse of the Werewolf

Most werewolf pictures afterwards featured human makeup, until in 1981 The Howling and An American Werewolf in London used puppets, extensive prosthetics, and even stop-motion animation to bring to life werewolves that were much more wolf-like, although much larger, more powerful, and often standing on two legs. In the CGI era, such films as An American Werewolf in Paris and Van Helsing gave us more wolf-like, fast-moving werewolves because, well, they can.

The puppet werewolf in American Werewolf in London

The puppet werewolf in The Howling

The CGI werewolf in Van Helsing

The earlier objections to depicting a werewolf as a wolf have vanished – CGI can give expressive faces to its creatures (just look at the fantastic work done in Peter Jackson’s 2005 King Kong) , they can perform exactly as needed, and the vast amount of work done on texture modeling and hair rendering means that they look as realistic as an unreal creature can look.

An interesting exception to the trend is the 2010 version of The Wolfman, directed, eventually, by Joe Johnston. While not exactly a remake of the 1940 film, it retains enough of the details to show its ancestry (right down to including the telescope at the Talbot family home). Legendary Hollywood effects artist Rick Baker, most noted for his apes and other hairy creations, begged to come aboard and reproduce Pierce’s makeup, so this film is a deliberate throwback to the “classic” humanoid Wolf Man. But it is sort of a fossil in the era of CGI werewolves.

The Wolf Man (2010)

In the future, aside from low-budget films and quick TV productions and the like, I predict few more werewolves done purely by makeup, and none of the Bunraku double-think of the 1940s, where the Wolf-Man stood in for the Wolf.

Afterthoughts

A few things that don’t quite fit into the above:

-

The properties of the Wolf-Man are a bit different in the 1941 film than they would be later on. As many have pointed out, the werewolf transformation takes place during a season, and not under the full moon. The last line of the poem is “when the autumn moon is bright”, which suggests an association with the moon, but the moon isn’t even shown in this film. The transformation clearly isn’t triggered by moonlight. In fact, in many of the night scenes the set is smothered in dry-ice fog. The second film to feature Larry Talbot as the Wolf-man, though, Frankenstein Meets the Wolfman, actually opens with a shot of the full moon. The poem is quoted twice in full during the film, with the last line changed to “when the moo is full and bright”. And moonlight is explicitly shown several times to turn Talbot into the Wolfman. In fact, when grave-robbers break into his crypt, where he’s lain for the past four years, buried in dried wolfbane, the moonlight falling on him not only turns him into the Wolfman but resurrects him from the dead, as well. For the next couple of pictures, in fact, Talbot’s motivation is to end his curse by finding a way to finally die for good.

-

Another feature of the first Wolf Man film is that you can identify the victim because the sign of the pentagram briefly becomes visible (to the untransformed Wolfman, at least) in the victim’s palm. This is a feature not made abundantly clear in the script, and which was never referred to in any later film. Furthermore, Maleva, the Gypsy woman, seems to know a second poem which can reverse the Wolfman transformation. She quotes it twice in the film. It begins “The path you walk is thorny/Through no fault of your own…” Probably because it is never cited in any other film (although Maleva appeared in Frankenmstein Meets the Wolfman, too), and is never quoted again, it is not remembered as the other poem that begins “Even a Man who goes to Church by Day…”

-

had no intention of making lycanthropy some sort of hereditary curse, and his original script has his protagonist entirely unrelated to the folks at the estate. Instead of that opening with Lawrence Stewart Talbot returning from America to the Welsh estate of Sir John Talbot, like Henry Baskerville returning from Canada to Baskerville Hall at the start of the Sherlock Holmes story The Hound of the Baskervilles, he is simply an unaffiliated Optical Engineer brought over to install and align that giant telescope Sir John has installed in his attic. As it is, Larry’s ability to work on a telescope that Sir John has already bought seems entirely too fortuitous. Siodmak wanted to show that anyone could be afflicted by the Curse of the WereWolf. But it makes you wonder why that entire business of the telescope is in there. I guess Siodmak simply used it as an excuse to get Talbot over from America, and to give him an excuse (to modern eyes, a pretty voyeuristic and creepy one) to introduce himself to the heroine. As an Optical Engineer myself, I was fascinated by this whole aspect of the film, which I didn’t recall from my many times watching the film. I even wrote a column about it for Optics and Photonics News ( I was a Teenage Optical Engineer in Optics and Photonics News pp. 22-23 December 2015). I contacted people familiar with the film and its background, asking if there were any optical engineers Siodmak may have known or lived near (there were many Optical Engineers in Los Angeles, as there still are, associated with both the military and the observatories, as Talbot’s character was said to be), but without finding any obvious links.