2014 saw the release of Dracula Untold, the first feature-length professional film from Irish director Gary Shore, from a script by American screenwriters Matt Sazama and Burk Sharpless. This was the first film made from one of their screenplays. Their other work is firmly rooted in Pop Culture.

So it shouldn’t be surprising that Dracula Untold is rooted not directly in Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula or in the history of Vlad the Impaler, from whom Stoker drew a very little of his inspiration, but more in the Francis Ford Coppola film Bram Stoker’s Dracula from 1992, with modern assumptions about vampires common to most films of the 20th century.

Dracula is often depicted as a darkly romantic villain, who entices women to him with seductive manners, an air of mystery, and hypnotic abilities that allows him to drink their blood, ultimately turning them into vampires themselves. But that’s not Bram Stoker’s Dracula at all. According to Pop Culture horror writer David J. Skal (author of the indispensable Hollywood Gothic: The Definitive History of Dracula in Book, Stage and Screen) Stoker depicted Dracula as a Darwinian predator, and unsocial and unsociable creature who took what he needed, and had no trace of romance or eroticism about him. It’s true that he has “wives” in the book, but these female vampires complain that he does not love them, or anyone . In the book, when Dracula goes off to find more profitable hunting grounds in England, he leaves them behind. The descriptions of his treatment of Mina Murray Harker and Lucy Westenra isn’t loving or romantic, but brutal and forced.

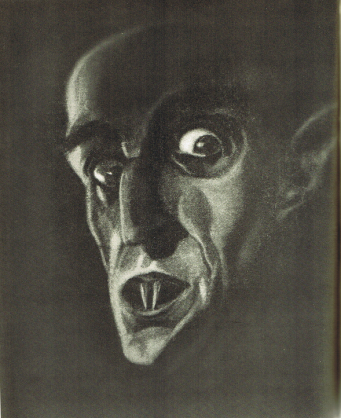

When F.W, Murnau adapted the story into film as Nosferatu in 1922, he adhered to this image. His “Count Orlock” was a bald, bulbous-headed, pointy-eared ghoul with a pair of rat-like incisors. The plague comes to town as he arrives, and he is the very personification of disease. When “Ellen Hutter” (the equivalent of Mina Harker) offers herself to this Ultimate Creep, it’s not because she’s being seduced, but because she is offering herself as a sacrifice to rid the town of the Vampire/Plague.

Nobody else could resist making Dracula somehow exotic and seductive, however. As Skal observed, when Hamilton Deane made the book into a successful stage play, he made it a “drawing room” play, and thus had to make Dracula into the sort of character who could be invited into a drawing room in the first place. The Darwinian asocial superman learned manners. The play was extensively rewritten by John Balderston for Broadway, where Hungarian actor Bela Lugosi took over the role, playing him as exotic East European Nobility. Afterwards, onstage and screen, the character was played by a series of actors who added sexiness to the exoticism, including Christopher Lee (a great many times), Frank Langella, Jose Greco, Gary Oldman, and others.

Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 film Bram Stoker’s Dracula fleshed out the story considerably, enlarging upon a few hints of Dracula’s background from Stoker’s original book, along with a great deal of material about one of Stoker’s inspirations, Vlad the Impaler, exhumed by writers Radu Florescu and Raymond T. McNally, starting off the film with an extensive prologue. This showed Vlad fighting off the Turks and having a loving wife, whose suicide at the false report of Vlad’s death drives Vlad to take an unholy vow that results in his becoming a vampire. All of this is far removed from Stoker’s selfish villain who attends the Devil’s own school of necromancy, and thus forfeits his soul.

Dracula Untold builds upon this framework, imagining a noble Vlad who defends his homeland , even at the risk of his soul, making an unholy bargain to obtain the supernatural help he needs, but becoming himself a vampire as a result. But the film ends on a positive note, as the ageless and undying Dracula meets a woman in modern-day London (not Stoker’s Victorian London) named Mina who uncannily resembles his long-dead wife Mirena, and it is strongly implied that she is the reincarnation of Mirena.

All of this (aside from the modern-day angle) is from the Francis Ford Coppola version, where Dracula meets Mina Murray in London and sees in her the reincarnation of his wife, who had committed suicide. He goes out of his way to seduce her and engage her romantically. (the movie’s tag line is even “Love Never Dies”) It should go without saying that there’s not an iota of this in Stoker’s book. Nor in any prior film or stage incarnation of the story. So where did it come from, and what are its roots?

It turns out that, although this is a very recent addition to Dracula lore, it has roots that go deep into Pop culture, and are almost as old as our modern incarnations of monsters – they go back to the time of the creation of modern Vampires, and Frankenstein, and stories of Mummies, to the beginning of the 19th century. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

The screenplay for Coppola’s film was the work of James V. Hart, a man who has written a number of screenplays and books, and produced films, all of which re-examine old and classic stories. He not only wrote the screenplay for Dracula, he co-produced it. He co-produced Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and wrote the screenplay for Hook, later writing a book about Captain Hook’s backstory. He wrote the teleplay for a TV version of Treasure Island and later wrote the script for Muppet Treasure Island. The man clearly has Pop Culture coursing through his veins.

In many ways, his version of Dracula was one of the most ambitious – he tries to put as many of the characters and incidents from the book onto the screen, including a great many that hadn’t appeared before. There’s a reason nobody did it earlier – Dracula is extraordinarily hard to turn into a coherent evening’s entertainment. It has far too many characters, and locations that are far apart. Even ignoring the Transylvanian location, I’ll bet most American viewers are under the impression that Dr. Seward’s establishment and Dracula’s Carfax are near London – they’re not. They’re set in Whitby, some 200 miles away. Yet in the book, Dracula, in wolf form, visits the London Zoo. In Coppola’s film, Dracula meets Mina in London. But Whitby is as far from London as New York is from Boston.

Lucy has not just one but three suitors. Theatrical companies tended to cut the number down, both for logistical reasons, and to not tax the ability of the audience to keep characters straight. For the 1931 film, the solicitor who goes to Transylvania is not Harker by Renfield, who accompanies Dracula to England aboard ship and is driven insane by the experience, thus becoming Dr., Seward’s patient. This eliminates a lot of questions about Harker’s travel, and explains Dracula’s interest in Renfield. In the 1979 John Badham film, the one with Frank Langella as Dracula, Lucy Westenra becomes Lucy Van Helsing, the better to explain the eccentric doctor’s interest in her case. Other films and stage versions have made other changes, coalescing characters, eliminating others, and re-arranging relationships in order to make motivations clear. It’s a fascinating study by itself.

All of which explains why it was that Hart’s screenplay made Mina Murray the re-incarnation of his own dead wife – it gave him a compelling reason to pursue her, and to take an interest in her. In previous film versions their only connection was that Dracula had seen her picture in Harker’s locket (“Your wife has a LUFFLEY neck!”) That’s not really sufficient motivation to have Dracula seize upon her as an interest after he’s exhausted Lucy’s blood. Furthermore, it makes that relationship more meaningful. Dracula isn’t just after his next meal – he is in pursuit of his Lost Love.

Screenwriters do this sort of thing all the time, particularly when adapting works from other media. In a film, with its typical length of ninety to 180 minutes, doesn’t allow a lot of time to develop the relationships and motivations that can be slowly built up over hundreds of pages in a novel., or to include a lot of extraneous characters that the audience will have trouble identifying and keeping straight. So a clear and simple motivation is a Good Thing, even if it does violence to the original spirit of the book. But modern audiences expect a somewhat sexy Dracula, anyway.

So Hart could have made up the concept by himself. But the idea of Dracula pursuing his Reincarnated Lost Love wasn’t original with Hart’s screenplay. It had been used before, and one suspects that the Pop Culture-savvy Hart would have known about this earlier use.

Dan Curtis, who came up with the supernatural-themed Soap Opera Dark Shadows in the 1960s moved on to produce and direct TV movies based on classic monsters. Besides versions of Frankenstein and Dr. Jeckyll and Mister Hyde, he also produced and directed a version of Dracula, starring Jack Palance. The screenplay was written by the legendary Richard Matheson, who was renowned for his work both in print and in screenplays. He was responsible for a great many of the Twilight Zone scripts. His novel The Shrinking Man would be filmed as The Incredible Shrinking Man, one of the more acclaimed B-movies of the 1950s. His own vampire novel I Am Legend had already been filmed as The Last Man on Earth, and would be filmed two more times.

Like most Dan Curtis productions, Dracula was filmed on a budget, but tried hard not to show it. Nevertheless, Dracula’s haunt in Carfax looks more like a well-kept suburban home than the dusty, crumbling Abbey usually depicted. Palance is an appropriately grim and not overly romantic character. But the reason given for his pursuit of Lucy Westenra is that she is the reincarnation of his dead wife. (Please observe that it is Lucy in this case who is Drac’s Lost Love, not Mina, as in the Coppola film and in Dracula Untold. Mina doesn’t even appear as a character in this version, and Jonathan dies in Transylvania at the hands – and teeth – of Dracula’s vampire “wives”).

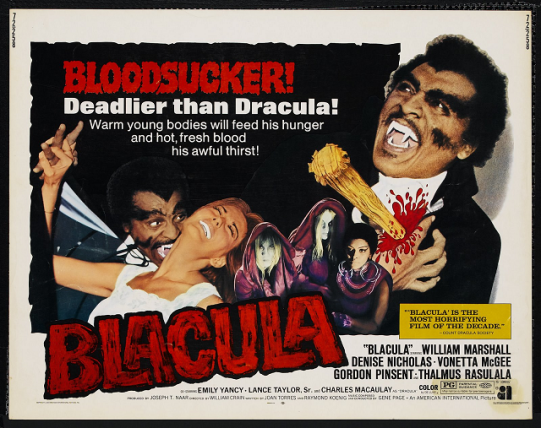

But Matheson was himself preceded by another film – the “Blaxploitation” vampire film Blacula, released a year earlier in 1972. In this film, African prince Mamuwalde appeals to Dracula (who he doesn’t realize is a vampire) for help in suppressing the slave trade. This is set in 1780. Dracula not only doesn’t help, he transforms Mamuwalde into a vampire and seals him in a coffin. He also imprisons the prince’s wife, Luva, who dies in captivity.

Flash forward to 1972. Mamuwalde’s casket is opened in Los Angeles, and Mamuwalde is finally released, He sees Tina Williams at the funeral of one of his victims, observes her resemblance to Luva, and is convinced that she is Luva reincarnated.

The screenplay for Blacula and for its sequel, Scream, Blacula, Scream, were written by Joan Torres and Raymond Koenig, who have no other listed credits. Exactly why they chose this trope to unite their two main characters isn’t clear.

So it seems that Torres and Koening, as well as Matheson, are responsible for introducing the idea of one of Dracula’s victims being the reincarnation of his Lost Wife. Prior to 1972 there is no hint of the idea.

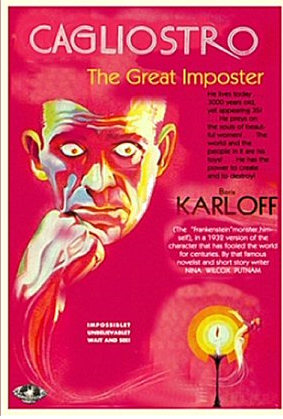

But even they did not, in all likelihood, originate the trope. There was an earlier case of a Hollywood Monster pursuing a woman because she was the reincarnation of his Lost Love. And it was a Universal horror film, at that. Carl Laemmle, Jr. , who was responsible for Universal’s successful run of horror films, asked story editor Richard Shayer to come up with a story that capitalized on the relatively recent opening of King Tut’s tomb. Shayer, in collaboration with novelist/screenwriter Nina Wilcox Putnam, came up with a screen treatment about the historical charlatan Cagliostro, who claimed to be 3000 years old. The link to Egypt was that he had started out there, keeping himself alive through magic and/or science.

The concept was handed off to John Balderston, the re-worker of Deane’s stage play for Dracula, and author of the screenplay for the Universal film. He had proven his worth to Universal studios by taking the mess of conflicting versions of Frankenstein , including Peggy Webling’s stage play and Richard Florey’s odd screen treatment, and crafting a filmable screen story.

Balderston similarly reworked Cagliostro, changing it completely. Gone was the 3,000 year old charlatan, replaced by the mummy Im-Ho-Tep, who was buried without the usual embalming procedures, and is awakened by the modern-day recitation of a life-giving spell. The script retains his powers, but makes them magical, not super-scientific.

Balderston had been one of the journalists present at the opening of Tut’s tomb, so he might have been indulging his own expertise as well as returning to Laemmle’s original vision. In any event, he introduced into the script the concept of Im-Ho-Tep pursuing Helen Grosvenor because she is the incarnation of his Lost Love from back in Pharaonic days, the Princess Ankh -es-en-Amon. The woman herself does not recall this (as neither Lucy nor Mina recall being Dracula’s wife) until the end of the film. At the conclusion, in the full persona of the Princess, she calls upon the goddess Isis to save her from the grisly process of death-mummification-and revivification that Im-Ho-Tep had in store for her. The statue of the goddess moves, blasting Im-ho-Tep with a radiant burst of magical energy, and he crumbles into dust.

Balderston himself had been a playwright, and before he had rewritten Dracula, he had a major success with Berkeley Square, a play about a man transported through time to the era of the American Revolution, and who meets his ancestors. Leslie Howard, who starred and co-produced, later appeared in a film version, and was nominated for an Academy award.

The play itself was re-imagined as the musical On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, in which the fantastic element was changed to a woman being reincarnated. It went on to become a Barbra Streisand movie.

In the 1940s Universal revived its horror film franchise, producing sequels, re-imaginings, and remakes. Four Mummy movies came out then – The Mummy’s Hand (1940), The Mummy’s Tomb (1942), The Mummy’s Ghost and The Mummy’s Curse (both 1944) introduce a new Mummy, Kharis, who has had his tongue removed, who never regains his fully human appearance (being always swathed in bandages) , and who is revived by “tana leaf tea” instead of a reading from The Scroll of Thoth. Nevertheless, the series revives a number of ideas from the first Universal Mummy film, including, in The Mummy’s Ghost, the idea of a modern woman being the reincarnation of Princess Ananka.

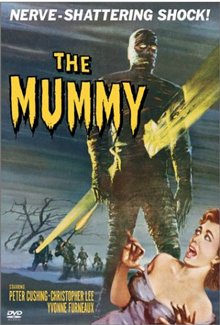

The Mummy got a new shot at life in a series of films made by Hammer Studios starting in 1959, with Christopher Lee playing a surprisingly agile Mummy. Sure enough, Kharis the Mummy is motivated by his search for the modern-day incarnation of Princess Ananka (even the names were taken from the 1940s Universal films).

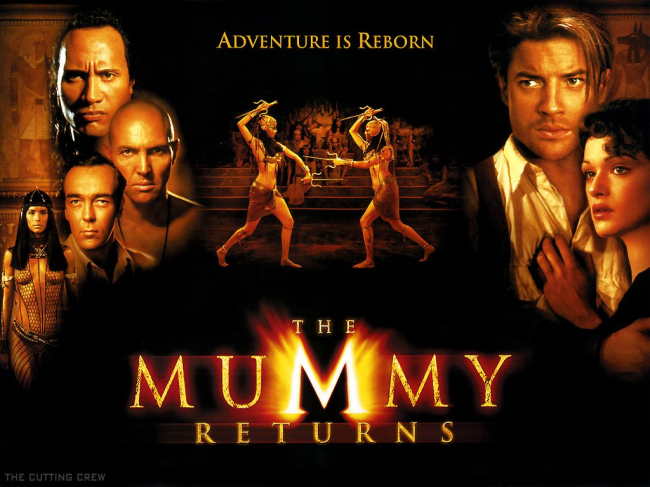

Finally, Stephen Summers made a very heavily revamped remake of the original Mummy film in 1999, but without the reincarnation angle. That changed with its 2001 sequel, The Mummy Returns, in which Im-Ho-Tep is revived with the help of a woman named Meela Nais, who is very consciously the re-incarnation of the Mummy’s love, Anck-su-namun, thus recreating the pair from the 1931 film. But in this version the Princess is by no means unwilling. It is further revealed that the heroine of this and the previous film is the reincarnation of Princess Nefertiri, a rival of Anck-su-namun, so there’s plenty of reincarnation to go around.

There’s one other instance of the Mummy’s Reincarnated Lover, from an obscure 1958 film from Vogue Films entitled The Curse of the Faceless Man, from a script written by veteran SF writer Jerome Bixby. Bixby wrote some very good screenplays, such as It! The Terror from Beyond Space (from which the script for Alien appears to have been lifted) and for Fantastic Voyage, among others, but this is arguably his worst. Although not explicitly stated to be such, the titular creature appears to be one of those plaster of Paris casts made from the hollows left by people killed and virtually vaporized by the pyroclastic flows and hot ash of the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE. This one is already in reconstituted form, though, needed no plaster. Before he was cremated, he was the Roman Quintillus Aurelius, and he loved a Roman lady to whom he gave a brooch. Now that he has been excavated, he believes that present-day artist Tina Enright, is the reincarnation of his love. She has the brooch, and she has dreams at night of being in ancient Rome, so it all seems to fit. At the end of the film, he carries the fainting form of Tina into the Mediterranean, and dissolves.

We thus have a parallel tradition of the Mummy’s reincarnated lovers to go along with Dracula’s reincarnated lovers, with all of it springing ultimately from the work of John Balderston. But is he really the source of it all? Despite his play Berkeley Square, he is certainly not the originator of the idea Reincarnation of a Lost Love as the motive for an astonishingly long-lived villain to interact with a modern-day hero or heroine

In 1885 H.Rider Haggard won fame as the originator of exotic and supernatural adventures in far-off places, usually in Africa. He made his mark with King Solomon’s Mines in 1885. But he felt he had achieved something remarkable with his novel She: A History of Adventure in 1887. The title character’s title is fully rendered as She-Who-Must-Be-Obeyed, and is truly named Ayesha. She is the ruler of the Amahaggar People in central Africa, and she is rumored to be thousands of years old. She was the lover of the ancestor of the hero, Leo Vincey, who has undertaken the expedition to Africa to seek out this woman, written about in family history. When she sees him, she declares that he is the very image of his ancestor Kallikrates (whose body she has preserved), and must be his reincarnation. Like Universal’s original mummy, she has various mystical powers, and the preservation of life is among them. She offers to give Vincey the treatment, as well. To prove that this treatment – which involves stepping into the Fire of Life – is harmless, she re-enters the Flame herself, and is rapidly reduced to dust.

Ayesha didn’t stay dead. Haggard revived her in Ayesha: The Return of She in 1905 (the very first instance I am aware of in which a fictional character who was undoubtedly killed at the end of a novel was brought back to life in a sequel. It would not be the last), in which it is revealed that the Flame of Life is a radioactive element (radioactivity having been discovered since the publication of She; the notion would be used in the Merian C. Coper 1934 film version of She)

It’s impossible to believe that Balderston was unaware of Haggard’s work. She made an enormous splash on its publication, and continued to be popular, between Haggard’s sequels (there were eventually three sequels, including one where she met Allen Quatermain, the hero of King Solomon’s Mines) and the motion picture adaptations of She.

Haggard’s involvement goes closer to Balderston’s Mummy script, though. He himself had been told that he was twice in previous lives an Egyptian – once a noble in 4000 B C E, another time as a minor Pharaoh himself (See Chapter 11 of his autobiography The Days of my Life ) He himself used the idea of reincarnated Egyptian lovers in his story Smith and the Pharaohs.

(It’s worth pointing out that Stoker himself flirted with the notion of an Egyptian Mummy reincarnated in the modern day, in his 1904 novel The Jewel of Seven Stars — “She is unlike her mother; but in both feature and colour she is a marvellous resemblance to the pictures of Queen Tera!” But Stoker’s novel lacks the idea of a reincarnated lover.)

So, it looks as if H. Rider Haggard is our source for the Reincarnated Lover trope. But we have to look further and see if there are any sources that Haggard himself drew from. What were his influences?

Fortunately, we know what they are – Haggard himself wrote about his inspirations in the chapter that he contributed to the 1887 book Books Which Have Influenced Me. So what DID influence him? The Arabian Nights. Three Musketeers. Robinson Crusoe. And the poems of Edgar Allan Poe.

We can dismiss the others as possible sources for reincarnation. But Edgar Allan Poe’s work is filled with absent and reincarnated women – Lenore, Annabelle Lee. But the strongest parallels are to his tales Morella and Ligeia. In Morella (1835) the narrator’s wife Morella, is fascinated by the philosophy of identity. She is pregnant, but in poor health. She dies in childbirth, but after proclaiming that part of her endures. Their child, as it grows up, develops into a duplicate of her mother. The father decides to have her baptized at the age of ten. When asked for her name, he instead replies “Morella”, at which the child says “I am here!” and dies. The implication is that the baptism returned the mother’s soul to a physical body. When they try to bury the body with her mother, they find the tomb empty.

Ligeia (1838) is similar in some ways. The title character (who seems to have no previous history) is obsessed with philosophy, and is convinced that, with a strong enough will, one can even overcome death. The story begins with an epigraph attributed to philosopher Sir James Glanville:

“And the will therein lieth, which dieth not. Who knoweth the mysteries of the will, with its vigor? For God is but a great will pervading all things by nature of its intentness. Man doth not yield him to the angels, nor unto death utterly, save only through the weakness of his feeble will”

Actually, no such quote appears in Glanville’s writings – Poe seems to have simply made it up for the purposes of the story. Ligeia dies, and the narrator remarries, but does not love his new wife. He builds her a bedroom decorated with Egyptian motifs (!), including sarcophagi. The idea seems to be that she is gathering the symbols of rebirth. She falls ill, and he takes laudanum. In his drugged state, he thinks that he sees the hair and eyes, not of his dying wife, but of Ligeia.

Poe’s narrators are frequently of the “unreliable” sort. In Morella he’s under emotional stress, and in Ligeia he has the additional burden of being in an opium haze, so Poe always has ambiguity on his side, but he is clearly suggesting the possibility of reincarnation of a sort in both stories, and of a Lost Love. Furthermore, in the case of Ligeia there is a tie to ancient Egypt, with its ideas of preservation of the dead for an afterlife that might involve physical bodies. Poe lived in the aftermath of the first craze over Egypt, prompted by the discoveries there during the Napoleonic Wars, and of the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, which allowed Thomas Young and Jean-Francois Champollion to work out the translation of the hieroglyphs. Poe himself wrote one of the first stories about a re-awakened Mummy (which suggested that their mummification was a procedure for a very physical and materialistic re-awakening), Some Words with a Mummy (1845).

So, we find that the Reincarnated Lost Love as an idea of philosophy and inspiration from Egyptian models. The idea of the reincarnated lover first haunts Poe’s tottering-on-the-edge narrators, but H. Rider Haggard saw the dramatic potential and the possibility of explaining motivations through such reincarnated lovers, over many thousands of years, and used it in his stories. John Balderston grabbed onto it for his original Mummy script for Universal, and the idea, providing a simple enough narrative explanation, found new life in the 1940s Mummy Films and two cases from the 1950s. So when Joan Torres and Raymond Koenig were looking for some way to explain the connection between his age-old vampire and a modern woman, they seized upon this trope, possibly influenced by the many Mummy movies. If they hadn’t, then Blacula might have consisted of nothing but a series of brutal vampire attacks. With this motivation, the movie becomes more of a love story, with human interactions and character development.

Did Matheson know about Blacula, or did he also get his inspiration from the Mummy movies? He might even have gotten the idea from as far back as Haggard. In any event, the idea went from Mummies to vampires to Dracula himself. From either Blacula or the Dan Curtis Dracula, it went to James V. Hart’s script for the Coppola film. (Is it possible that Hart hadn’t heard of the prior vampire films? Certainly the people at Saturday Night Live didn’t think so. On their November 21 1992 broadcast – Season 18, Episode 7 — they had a skit entitled Bram Stoker’s Blacula, starring comedian Sinbad as the title character, in a double-barreled Afro that recalled the weird hairstyle Gary Oldman’s Dracula sported in the Transylvania scenes of the 1992 film. ) And from the Coppola film to Dracula Untold.

The trope has now taken on a life of its own. It even has its own page on the website TV Tropes What had been an original (if supernatural) way to link two people from completely different places with completely different backgrounds became a convenient trope, then a commonplace. We now have a New Myth of Dracula’s background, completely divorced from Stoker’s original story and his conception of the character. But it has been sanctified and approved by two movies now, so it’s likely to become part of our shared social mythology, like the idea that Vampires Dissolve in Sunlight.

Added February 6 2017 — Yet another Vampire film about searching for a Reincarnated Lost Love.

I hadn’t realized that the 1993 film Dracula Rising has basically the same idea. Some sources give the release as 1992, which is significant.

The film stars Christopher Atkins (best known from The Blue Lagoon) as Vlad Dracula, the Son of the more famous count. He seeks Theresa (Stacey Travis, who was much better in Ghost World and Hardware), who is the reincarnation of his lost love, in 1992 Los Angeles. From all accounts, this is an amazingly dull and boring film, enlivened by a little soft-core in the middle. Its chief interest is that it came out about the same time as Francis Ford Coppola’s own Dracula, and lifted its main plot device.This isn’t all that surprising — Roger Corman was the producer, and he had a penchant for that sort of thing. In 1993 he rushed his Dinosaurs-recreated-with-DNA movie Carnosaur into the theaters four weeks ahead of the similarly themed (and bigger budgeted) Jurassic Park.

Added March 11 2017:

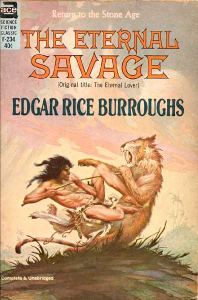

Yet another case of The Reincarnated Lover I had been unaware of — Edgar Rice Burroughs’ The Eternal Lover. It was reprinted in the 1960s by Ace books as The Eternal Savage, I suspect to appeal to those pre-teens not interested in lovers.

The novel concerns Nu of the “Niocene” (an era Burroughs invented for the purposes of his narrative), 100,000 years ago. His lover is Nat-Ul. When Nu finds himself translated through time to the present day, he meets Virginia Custer of Beatrice, Nebraska, who is the image and reincarnation of Nat-Ul. They eventually return to the Niocene.

Burroughs’ story appeared in two parts in All-Story Weekly as The Eternal Lover on March 7, 1914 and as Sweetheart Primeval on February 13, 1915 (a day before Valentine’s day!).

It was published in book form in 1925.

The story’s characters are linked to Burroughs’ Tarzan series (Virginia is a guest at Tarzan’s African reserve) and to The Mad King (published in alternating issues of All-Story with this one) — in which Virginia’s brother appears.

Nu of the Niocene is obviously later than Haggard’s She, but pre-dates most of the other cases here. And at 100,000 years between reincarnations, it certainly wins the time-span derby.

Added October 16, 2017

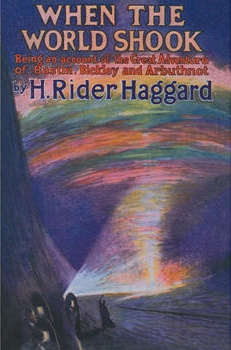

Well, I was wrong — there’s a “reincarnated lover” story with a gulf between the lovers of much more than 100,000 years. It’s H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, first published in 1919. Here’s the original dust jacket:

The novel tells the story of Humphrey Arbuthnot, whose wife Natalie (who is apparently in perfect health) suddenly sickens and dies. Before she does, she tells him to travel, and they will meet again. Long after her deathj, he travels with his two unlikely friends, the atheistic Doctor Bickley and the credulous and a bit fanatic clergyman, Bastin, and with Humphrey’s dog, Tommy.

They end up wrecked on a South Pacific island with a pyramid in the center of a lake, which opens to admit them. Inside they find two crystal “coffins”, one containing a beautiful young woman, the other an old and heavily bearded man. The two, who have evidently been in a state of suspended animation, awake. (This is the earliest appearance of this trope I’m aware of). The man is Oro, who is worshiped by the natives of the island as a god. The woman is his daughter, Yva. They have been sleeping for 250,000 years. Oro had been the ruler of the Earth in his time, the leader of a cadre of very long-lived super-scientists. The ordinary people, jealous of their long lives and advantages, revolted, and so Oro destroyed their world, sending earthquakes and a flood.

Yva and Arbuthnot fall in love, and in the course of his dreams he realizes that Natalie and Yva are conmingled. Natalie isn’t exactly the reincarnation of Yva, but Yva has absorbed Natalie’s persona. And Arbuthnot is the reincarnation of Yva’s lost love, who was slain by Oro.

Oro learns about the modern world and is not pleased, and decides to destroy our modern world, as well. But as he prepares to do so, Yva sacrifices herself. Oro knows that he will himself dies before he gets another opportunity. Arbuthnot and his friends go back to England, and shortly thereafter Arbuthnot dies, and is buried next to Natalie.

So this story, another of Haggard’s Reincarnated Lover stories, ups the ante to a quarter of a million years.

Cover of 1978 Paperback edition