There is magic in names… and the mightiest among those words of magic is Atlantis. When we have pronounced the word, nothing definite is revealed, but it is as if a sudden shaft of sunlight smote the darkness of the past, allowing us a glimpse of cloud-capped towers, and gorgeous palaces, and solemn temples; and it is as if this vision of a lost culture touched the most hidden part of our soul.

–Christina Alberta’s Father (1925) by H.G.Wells

Part I — Atlantis

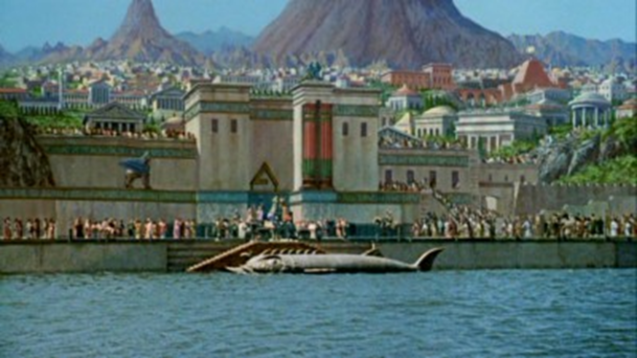

Atlantis has been the setting for fantastic fiction, movies, comic books, and the like throughout my lifetime. The legend of Atlantis goes back to Plato, and some would argue that it is even older. My introduction to Atlantis was with the George Pal movie Atlantis, The Lost Continent from 1961, a film which I loved as a kid.

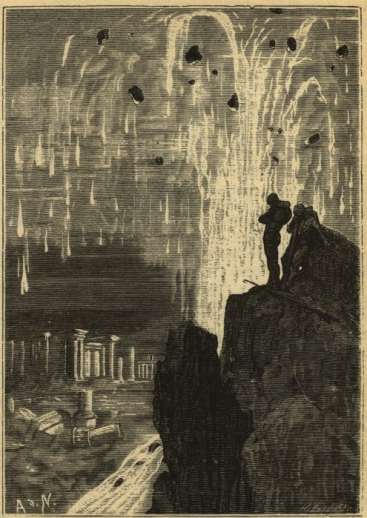

What’s most surprising to me is the fact that, although I was raised on the notion of Atlantis as an advanced culture with highly advanced science (or, by some accounts, magic), this has not been the image through most of history. Atlantis was seen as an early and powerful culture, but not especially high in wonders or technology. It is a sobering thought that when Jules Verne had his Captain Nemo showing off the ruins of Atlantis in his 1870 novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, he was one of the last stewards of the old view of Atlantis. Surprisingly, the image of Atlantis put forth by The Father of Science Fiction had nothing at all of the fantastic about it – it was simply the remains of an old and sunken culture that Nemo was in a unique position, as sole explorer of the undersea world, to appreciate.

Illustration of Captain Nemo looking at the Ruins of Atlantis for 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

Atlantis with its submarines, flying machines, magical metals, elixirs of youth, eternal preservation, prehistoric animals, power crystals, and other scientific and magical wonders had not yet appeared in the public consciousness. The combination of that power with Atlantis’ fabled wickedness (that lead somehow to its destruction) made a potent image for the writers of fiction and makers of films. But, like so many images of Pop Culture, such as the modern image of vampires, of Frankenstein Monsters, or Invisible Men, Mechanical Men, Invading Aliens, Heavier than Air Flight, Revived Mummies, Werewolves, Giant City-Destroying Monsters, and Space Ships, it has come into the world only since 1800. Here is how, and why.

As every article about Atlantis points out, our ultimate source for the story is two dialogues of Socrates written by Plato – Critias and Timaeoa. (there was apparently to be a third, but it was never written, and the Critias was itself not completed), dating from about 360 BCE. The Timaeus tells that Solon visited Egypt, where he learned from the sages there the story of Atlantis, which waged war upon Athens in its early years. A fuller description of Atlantis was postponed until the dialogue Critias, which gives a physical description of Atlantis.

Atlantis is described as an island (not a “continent”), albeit a large one. It is as large as Asia and Libya put together. But “Asia” meant what we would call “Asia Minor” – that is, essentially modern Turkey. And “Libya” means not the modern nation, but a portion of Northern Africa. That’s still a rather large piece of real estate, and one that wouldn’t fit in the Mediterranean. Just as well, then, that it is beyond the Pillars of Hercules in the Atlantic Ocean. It might be as large as England or Greenland from this description.

Its inhabitants were said to be descended from five pairs of twin sons of Poseidon. The main palace was built in the center of the island within a series of concentric moats, with a canal leading to the sea, and walls around each ring, with walls of multicolored stone, decorated with the metals brass, tin, and orichalcum (literally “Mountain Copper”, although later interpreted as “gold copper”. Th3ere has been no shortage of speculation about its true meaning).

Nine thousand years before the time of the dialogue, the Atlanteans embarked on a war of conquest, invading the Mediterranean and conquering and enslaving the countries. An alliance lead by Athens resisted them, until, in a cataclysm lasting a single day and night, the island sank into the ocean.

It seems most likely that Plato was telling a parable about the idealized ancient city of Athens nobly resisting the corrupted, warlike Atlanteans, with the Atlanteans punished by the loss of their entire homeland. The vast antiquity of the tale, the absurdly symmetric geography of the island, the five sets of twin sons all seem too artificial to be believed, even in an era that held with the divine ancestry of kings. There have been many – a very great many – suggestions as to the origins of the story and the “real” location of Atlantis. If you’re of my own age, though, the dominant suggestion is that it is a dim recollection of the destruction of the island of Thera by the supervolcano Santorini, which is held to be the source of the destruction of the Minoan civilization about 3,600 years ago. The massive eruption and explosion (due to sea water coming in contact with a large amount of molten magma) resulted in huge ash deposition and megatsunamis. It would not be surprising if knowledge of such an event suggested the story – but did it? I think that the drama of the geological event and its potential have blinded most people to the immense gulf of time between the event and the story of Atlantis.

A more proximate event, much closer in time and space to Plato’s, and therefore a more likely inspiration is recorded in The Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, written contemporaneously with the was from 431-410 BCE, and therefore significantly predating Plato’s dialogues. Thucydides describes a series of earthquakes around 426 BCE, with the sea receding and subsequently rushing back in to inundate part of the city of Orobaiai in the Greek region of Euboia. (This sort of recession of the sea followed by a return that travels farther overland than the water originally covered is often described in seismic literature. It happened in the Alaskan earthquake of 1964). At the same time there was a similar inundation on the island of Atalantë of the coast of Opuntian Locris, which carried off part of a fort and wrecked two ships. The inundation by rce, first pointed out by John Francis Arundell in 1885, is that Plato cribbed the physical description from the Pleripus of Hanno, which described a voyage through the “Pillars of Hercules” out into the Atlantic, where they landed on the coast of Africa. He makes a good case that the description of the Atlantean plain derive from Hanno.

For more than 2000 years the story of Atlantis survived, sometimes as history, often as allegory. Probably because of the ideal nature of Atlantis in its early days, before it became corrupted into a world-conquering Evil Empire, “Atlantis” became the name and title of literary Utopias. Thus Francis Bacon wrote The New Atlantis in 1627, describing an ideal society on the island of Bensalem in the Pacific. Thomas Heyrick wrote the satiric poem also called The New Atlantis in 1687, and in 1709 the English author Delerivier Manley produced the dystopia New Atalantis.

So when Verne had his undersea Captain Nemo come across the sunken island of Atlantis west of the Azores, he was simply describing a lost city from pre-classical times in a location consistent with the way it was described by Plato, and with no special high science or technology. All other accounts of Atlantis and its spiritual descendants were pretty consistent with this. All that was about to change because of a book by an early writer of science fiction, fantasy, horror, and historical fiction (although most are unaware of his efforts in these directions) who wasn’t even writing about Atlantis.

Edward Bulwer Lytton (1803-1873) is today remembered for a contest named after him (which seeks the worst opening sentence for a story, because he famously began a novel with “It was a dark and stormy night”) and as the author of The Last Days of Pompeii. In his time, however, he was an unbelievably popular author, along the lines of a Stephen King. He wrote plays, straight fiction, historical fiction, horror, and even a little proto-science fiction. He’s the one responsible for the phrases “the pen is mightier than the sword”, “pursuit of the almighty dollar”, and “the great unwashed”. Ironically, although he did open his 1830 novel Paul Clifford with “It was a dark and stormy night”, he was not the first to use that portentous phrase – Washington Irving had used it earlier.

Bulwer Lytton’s role in our story comes from one of his last works, his 1871 novel The Coming Race, one of the first of the “Lost World” novels about an explorer coming upon a hidden country and culture unknown to the outside world, and arguably the one that precipitated the deluge of Lost World novels that continues to this day.

In the novel, the unnamed narrator and his geologist friend explore a cavern and discover the city of the Vril-ya, angelic beings who live underground in a somewhat Egyptian setting. They control he power of vril, a sort of superscientific or occult force, using special staffs. They have flying machines powered by vril. This source of power is rather like The Force in George Lucas’ Star Wars series. It can be used to heal or to destroy, it permeates everything, and the ability to control it is somewhat hereditary.

As Bulwer-Lytton revealed in a letter to a friend, he had in mind something like electricity, with its many manifestations and its ability to perform creative and motive features and to destroy. In the novel, the Vril-ya are descendants of antediluvian people who took refuge underground, but it is hinted that they may one day reclaim the surface from modern man.

Bulwer-Lytton’s vril became immensely popular, with societies devoted to it. Products were named after it, including Bovril, a British product first created in the 1870s as a sortof dehydrated beef extract, from which could be made “Beef Tea”/bouillion. The name came from a combination of “Bovine” and “Vril”. It’s still sold today There were Vril societies in England and on the Continent.

One person influenced by the mystique of Vril was Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831-1891), the Russian émigré occultist who claimed to have visited occult master in Tibet and to have contact with spirit guides. She founded Theosophy and the Theosophical Society to formalize her philosophy and paranormal vision of the world. She claimed that Bulwer-Lytton’s idea of Vril was virtually identical to a concept in her philosophy, and took to calling it Vril as well in her books Isis Unveiled (1877) and The Secret Doctrine (1888).

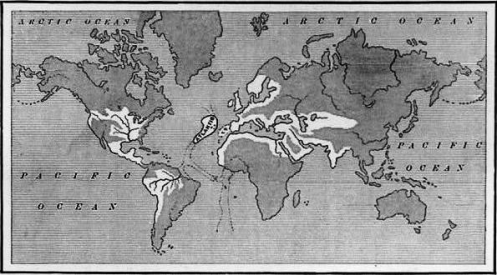

Blavatsky conceived of the history of mankind as a succession of not-quite-human Root Races that inhabited lands now lost, including Atlantis. The Atlanteans races, including the Toltecs (not the group called that today, but ancestors of the American Indians) had a civilization that peaked between 900,000 and 1 million years ago and had vril-powered airships. There was a series of wars between Atlanteans practicing black magic and white magic, and ultimately the continent sank in 9564BCE. William Scott-Elliott wrote down a Theosophical account entitled The Story of Atlantis and Lost Lemuria (Lemuria was another lost continent, but in the Indian Ocean) in 1896.

Another occultist who became obsessed with Atlantis was Edgar Cayce (1877-1945), called “The Sleeping Prophet” from his practice of going into sleeplike trances, during which he divined the causes of people’s illnesses and also saw visions. He had a set of visions about Atlantis in the 1930s and 1940s, which were recorded by his followers. Many of these were published in 1968 as Edgar Cayce on Atlantis, but much of this was known outside Caycean circles well before that.

Cayce, too, believed in a multiplicity of races, although they were not as flamboyant as the Theosophical ones. The Atlanteans had a crystal that could absorb the power of the sun, called the Tuaoi Stone or firestone. They could control electricity and had flying machines, and controlled the “natural forces”. They lived from 100,000 years ago until about 28,000 BCE many emigrated to other places. The final destruction took place in 10,000 BCE.

Parallel with all these mystical writings on Atlantis, however, were two other threads, which featured a vision of Atlantis almost as exotic, and just as unlike the image of Atlantis as it was prior to 1870.

The first of these was the blooming literary career of a Minnesota politician named Ignatius Loyola Donnelly (1831-1901). At the age of twenty six he moved to Minnesota from his native Philadelphia, among rumors of financial misdealings. Within three years he had become the Lieutenant Governor of the state, only the second to hold that office. Afterwards he served as a member of the US House of Representatives for six years, then served several stints in both the Minnesota House and its Senate.

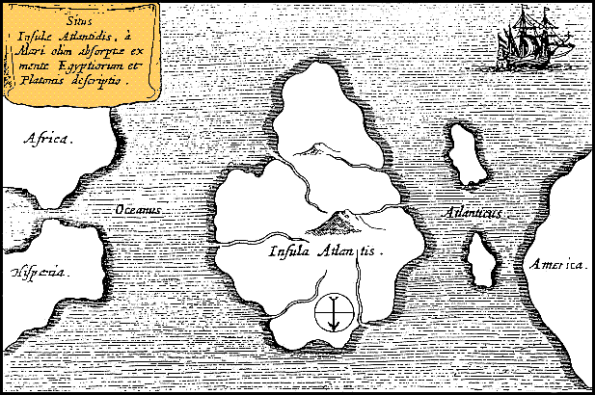

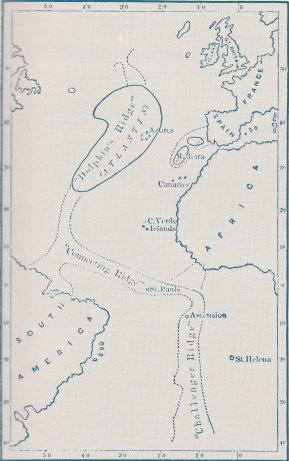

Between his service in Washington and in Minnesota he began to write. Today we would call it “crank” literature, but they were well-written and considered examples of it. He wrote a book “proving” that Francis Bacon wrote the plays of Shakespeare, and another in which he set down his notion that the Biblical Flood was caused by a near-collision with a comet. But his first book made the biggest splash, and is still in print today. Atlantis: The Antediluvian World was his magnum opus, Published in 1882, it set out his notion that the Continent of Atlantis really did exist along the newly-discovered “Dolphin Ridge’ (part of what we today call the Mid-Atlantic Ridge), that civilization started there, and that colonies of Atlantis started in Egypt, Greece, Mexico, South America, and elsewhere are but echoes of its high civilization, and that from the similarities between these many widely separated cultures we can see their common origin. Atlantis sank, just as Plato said, and its inhabitants fled and settled in the colonies, which were now the centers of civilizations.

Map of Atlantis from Ignatius Donnelly’s Atlantis — The Antediluvian World

Donnelly illustrated his theory with many line drawings showing the similarities between Old World and New World pottery, writing, pyramids, architecture, and the like. He quoted the work of those who claimed to have translated the American codices. His style and illustrations were really not that different in appearance from serious archaeological works, especially to the eye not accustomed to them. Place Donnelly’s book side by side with something like Arthur Bernard Cook’s Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion and they look quite similar. Donnelly’s book was immensely popular, and it certainly added to the popularity and mystique of Atlantis. It may even have precipitated Blavatsky’s own work on Atlantis. Isis Unveiled barely mentioned it, but The Secret Doctrine has quite a bit about Atlantis, and it followed Donnelly’s book by six years.

Donnelly’s book also introduced something new. Although he claims it is based on Plato’s dialogues (which he quotes, at length), his theory is very different from the story Plato tells, and he evidently thought that Plato, through the years intervening between the sinking of Atlantis and his telling of the story, must have gotten it wrong. In Plato, Atlantis is an old civilization, but quite separate from the kingdoms and cultures of the Mediterranean. Its interaction with Greece starts when they attempt to conquer Greece, along with the other nations of the Mediterranean, and they stop when their island sinks. In Donnelly, however, Atlantis is the Mother of Civilization. There was no need for Atlantis to conquer Greece or the other nations around the Mediterranean (or of the unknown New World), because they were started by Atlantis, and were offshoots of that culture and civilization. That’s how all those other civilizations ended up with replicas of the Atlantean culture. In Plato, Atlantis’ culture has nothing to do with those of Greece, Egypt, Phoenicia, and elsewhere. (In addition, of course, the Theosophists with their Seven Root Races and outrageous time scales gave us an Atlantis with its own culture, but which they ultimately exported to the rest of the world, as in Donnelly)

Map of Atlantis and its Colonies (in white) from Ignatius Donnelly’s Atlantis – The Antediluvian World

Donnelly’s Atlantis didn’t have flying vehicles, vril, or magic, but Donnelly did think that the Atlanteans were technically more advanced than any other ancient people – they just hadn’t advanced as far as 19th century science. They had magnets and the magnetic compass. They likely had gunpowder, iron, paper, and silk. They also had advanced Civil government, agriculture, and astronomy. Furthermore, he thought that they passed a lot of this information on to people living on both sides of the Atlantic after the continent sank, and that it was gradually forgotten until rediscovered later on.

The other major thread of the pop culture image of Atlantis was in popular fiction. After Donnelly provided the rational-appearing underpinnings, and the Theosophists had introduced the Bulwer-Lytton idea of exotic scientific or magical powers and devices, that idea expressed in the epigraph at the start of this essay became irresistible. The speaker of those lines, the Father of Christina of the title, was one of those deluded people who believed himself the reincarnation of an inhabitant of Atlantis – and there were plenty of these folk as well. But for many Atlantis was an exotic and enticing setting for stories. Some of these stories were frankly utopias for some particular philosophy, in the manner of Bacon and other earlier writers of Atlantis, but now the stories were baited with the lure of magic or high tech. To many others, Atlantis was just a good place to set your story. The popular press was becoming a force, in the next century story magazines would proliferate, and their need for stories was immense. This was fertile ground for the science fiction and fantasy and romance writers.

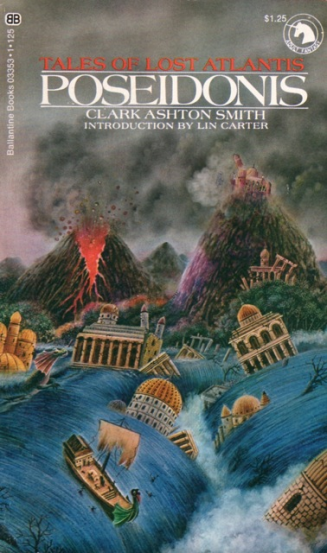

I won’t try to even begin to list all of them. Most were not particularly memorable, especially if it was a utopia type of story, and you didn’t subscribe to that particular philosophy. L. Sprague de Camp, in his book Lost Continents lists several stories and books, but I have to admit that even I, a fan of fantastic literature of the period, haven’t heard of most of them. I came of age in the 1960s and 1970s, when paperback publishers like Ace reprinted many of the older and cheaper stories, and when Lin Carter at Ballantine Books tried to revive interest in adult fantasy. A lot of the magazine and hardcover books were reprinted then, but that was some time ago, and modern readers may find my list as out of date and obscure as I find many of de Camp’s references.

There were several basic situations. Stories might be set in Atlantis itself, generally just before and during its Fall. They might be set in islands or colonies remaining just after the Fall. They might be set in the present day, with the protagonist discovering Atlantis, or inhabitants of some remaining colony of it. Atlantis, of course, was supposed to have sunk, but writers could place Atlantis in all sorts of unexpected places – in the Arctic, in the Sahara, or some other odd place. In this, they were duplicating the efforts of the Believers in Atlantis, who maintained that the land rally had existed once, but that people were mistaken about its location. (De Camp’s book has an appendix listing interpretations of where “Atlantis” really was. It runs for five pages). The most interesting location is undersea – Atlantis really DID sink, but it’s still inhabited by the Atlanteans. They either enclosed their city in a water-proof dome, or else they developed gills and live on as mer-people in their sunken realm.

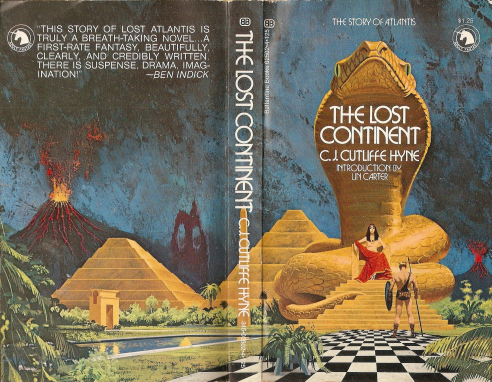

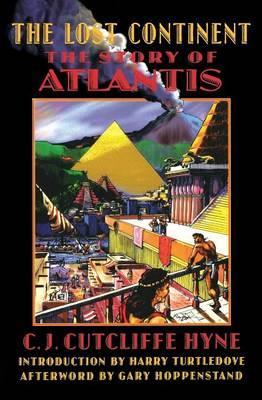

One of the first books about Atlantis is arguably also the best. C.J. Cutcliffe Hyne was an immensely popular novelist in his day. But, like Bulwer-Lytton, most of his works have been forgotten. You can find some of them on the internet, because this medium has as great an appetite for inexpensive material as any other new medium. His novel The Lost Continent: The Story of Atlantis (1900) has been reprinted multiple times, in both hard print and as an e-text.

And the book delivers. It starts out with a framing story of two explorers coming upon a set of wax tablets that record of the life of Deucalion, a priest-administrator-governor of Yucatan, a colony of Atlantis. Told in the first person, it tells of his recall to the main Continent of Atlantis. It’s clear that Cutcliffe Hyne derived his background from Donnelly. Atlantis is the Colonizer, not the Conqueror, and Deucalion is an able, fair, and wise governor. Atlantis has colonies in Europe and Africa, as well, and is spreading its culture through the world.

He ramps up the “Wow” factor over Donnelly’s vision, but doesn’t go anywhere near as far as the Theosophists. Deucalion’s world contains prehistoric animals, suggesting great age. He writes of Cave Bears and Cave Tigers (presumably saber-toothed) and mammoths, and the seas still harbor plesiosaurs that sometimes attack ships. Their technology includes crystals that can gather the power of the sun and release it in such a way as to propel their ships, which require neither galley slaves nor sails.

In any event, Cutcliffe Hyne seems to have been the first to draw together all the strands that had been building toward this moment – An adventure story with parallels in the present about an exotic ancient civilization possessing strange beasts and magic and technological wonders that because of its moral failing “falls” as literally as Poe’s House of Usher. It’s all very satisfying, which undoubtedly why it has remained so popular. But it has never, as far as I know, been adapted for stage, screen, or graphic novel.

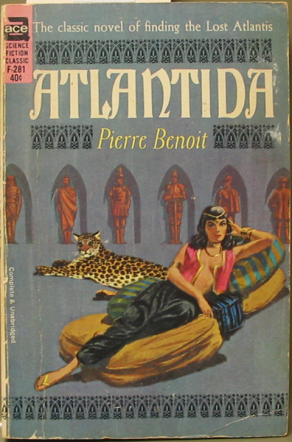

Pierre Benoit had an unusual Atlantis in his novel l’Atlantide (1919, translated to English as Atlantida a year later). Her “Atlantis” isn’t even an island, but a city in the middle of the Sahara (where some Atlantis-hunters had been supposing it to be since 1868). In his novel, two French officers serving in North Africa are drugged and abducted by Tuaregs as mates for Queen Antinea, the current ruler of the Atlantean people.

It was arguably the pulp magazines that provided the most fertile ground for Atlantean fantasies. J. Allen Dunn wrote The Treasure of Atlantis in 1916, a fantasy about descendants of the Atlanteans who fled to South America. It appeared in All-Around Magazine. Edgar Rice Burroughs’ hero Tarzan encountered descendants of Atlantean colonists in the Lost City of Opar in the second Tarzan novel, The Return of Tarzan, which first appeared in New Story Magazine in 1913. It returned in Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar, which was serialized in All-Story Cavalier Weekly in 1916. It re-appeared in several later Tarzan novels. Opar is ruled by the Evil Queen La, who wants Tarzan as her mate. One can see a pattern here.

Something different was provided by the fantasy author and artist Clark Ashton Smith, who created interesting otherworldly milieus for his works of fiction, including the imaginary French medieval region of Averoigne, the northern land of Hyperborea, the future continent of Zothique, and the land of Poseidonis, a remnant of the otherwise sunken continent of Atlantis. He began writing about Atlantis with his poem Atlantis in 1912, but the bulk of his Poseidonis stories were written in the 1930s. Smith’s stories are heavily influenced by the Theosophical vision of Atlantis (although populated by very human inhabitants), and concern magical happenings. They appeared in the pulp magazine Weird Tales, and were much later gathered together (along with unpublished tales of Poseidonis) by Lin Carter and published in 1973.

Smith, in turn, heavily influenced other writers. One of these was fellow fantasy-writer Robert E, Howard, with whom he corresponded. Howard had himself created an Atlantean hero, Kull, who was another usurper in the style of Phorenice. Howard’s Atlantis doesn’t owe much to earlier traditions – it’s simply a convenient otherworldly setting for Howard’s stories of magic. Far from being a high tech realm, it resembles the Roman Empire in technology and organization. There are magical happenings (some by the skull-faced wizard Thulsa Doom) , but magic plays no big part in the running of his Atlantis. Howard’s work appeared in several pulp magazines, but chiefly also in Weird Tales. Howard also wrote his own entry in the Fu Manchu-inspired “yellow peril” type of story, Skull Face. But the title character, named Cathulos (whose name is possibly an in-joke meant to resemble Cthulhu, the creation of another of Howards correspondents, H.P. Lovecraft), is revealed to be an ancient survivor of lost Atlantis (and who resembles Thulsa Doom) (Howard’s later and more famous creation, Conan of Cimmeria, owes a lot to Kull – his first story is a rewriting of Kull’s first story – and the ancient “Hyborian Age” that he lives in probably owes its name to Clark Ashton Smith’s Hyperborea.

Howard committed suicide at the age of 30 in 1936, and his editors at Weird Tales wanted something like Howard’s Conan stories to fill the gap. They commission science fiction and fantasy writer Henry Kuttner to write a similar series, Elak of Atlantis. He produced four stories in the series between 1938 and 1940. Elak’s Atlantis resembled Howard’s.

Arthur Conan Doyle jumped onto the bandwagon, giving the world the profoundly disappointing The Maracot Deep in 1929. Professor Maracot, virtually a clone of Doyle’s Professor Challenger, dives into the trench named for himself in a special diving bell and discovers an undersea city of Atlanteans living in domes and wearing diving equipment. The novel ends with an embarrassingly literal duel with the devil. This product of Doyle’s Spiritualist beliefs is not among his best works. That idea of Sunken Atlantis under a crystal dome had first appeared in 1906 in David M. Parry’s The Scarlet Empire (which de Camp calls “well-known” , but which is pretty obscure these days). It was used in several stories of Atlantis in the 1930s. It was also used in the low-budget 1936 Republic serial The Undersea Kingdom, in which Unga Khan seeks to conquer Atlantis (which looks suspiciously like Southern California) and then the surface world. He is opposed by “Crash” Corrigan, US. Naval Officer and virtually a clone of hero “Flash” Gordon. The Atlanteans have modern-looking tanks, rockets, robots, and television-like viewers.

(Sprague de Camp himself added to the Atlantis theme, writing The Tritonian Ring (1951) and other stories set in the lost continent of Pusad, whose name was later corrupted (in the continuity of his stories) to Poseidonis. He also “borrowed” Thulsa Doom from Howard’s Atlatean stories (it had actually already been done for the 1982 Conan film) for the tie-in novel with the 1982 movie Conan the Barbarian.)

Atlantis made an attractive setting for comic book characters – but only as a setting, and almost invariably of the “sunken city of merpeople” type. Bill Everett created Prince Namor, the Sub-Mariner, who was supposed to appear at first in Motion Picture Funnies Weekly, a “giveaway” comic to be distributed at movie theaters. That fell through, and so his adventures first appeared in Marvel Comics #1 in 1939. Namor, with his pointed ears and winged feet, was the son of a human ship captain and a princess of sunken Atlantis. He could breathe on both land and underwater and could fly, had immense strength, and could control sea beasts. He frequently waged war on the surface people, but sometimes fought for them (especially against the Axis powers after WWII started). The character is one of the few that continued into the 1950s, and was revived after a brief hiatus in the 1960s “Silver Age” of comics, with no more than small changes in his backstory. Sometimes he ruled as prince over the sunken City of Atlantis. The character continues in the Marvel stable of characters today.

Marvel Comics’ Prince Namor on the Throne of Atlantis

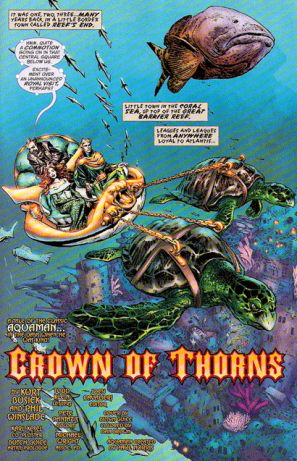

Two years later Paul Norris and Mort Weisinger created their own underwater hero, Aquaman. He was originally the son of a widowed undersea explorer who discovered the sunken and uninhabited Atlantis and raised his son there. He eventally gained the ability to breathe underwater and control sea creatures. Like Namor, he continued on into the 1950s, and was revived for the 1960s “Silver Age” But by that time his backstory had changed. Now he, like Namor, was the son of a human father (a lighthouse keeper) and Atlanna, a mer-woman outcast from undersea Atlantis. Aquaman, too, continues (although they continue to tinker with his backstory), and is currently being introduced into DC-based movies.

DC Comics’ Aquaman in the Royal Atlantis sled

Both the DC and Marvel universes also hosted other Atlantises – Superman met the literal, fish-tailed mermaid Lori Lemaris from the undersea city of Atlantis (which appears to be unrelated to Aquaman’s Atlantis, with its human-legged water breaters), and she continued on as a character. Marvel featured an underground empire of Atlantis in the early 1960s, which was revived in the 1970s. Again, unrelated to Namor’s Atlantis.

In 1954 Carl Barks wrote and drew The Secret of Atlantis, a 32 page Uncle Scrooge adventure in which Scrooge discovers a sunken city of Atlatis, populated by water-breathing mer-people, the descendants of the original air-breathing population. They are also acknowledged as the originators of civilization and language (which is why they could understand Scrooge), which means that this piece of wonderful fluff actually has stronger ties to the Atlantis tradition than the DC and Marvel uses, which treat Atlantis merely as a situation and setting. The story continues to be reprinted.

Uncle Scrooge and Donald Duck discover sunken Atlantis in Carl Barks’ The Treasure of Atlantis

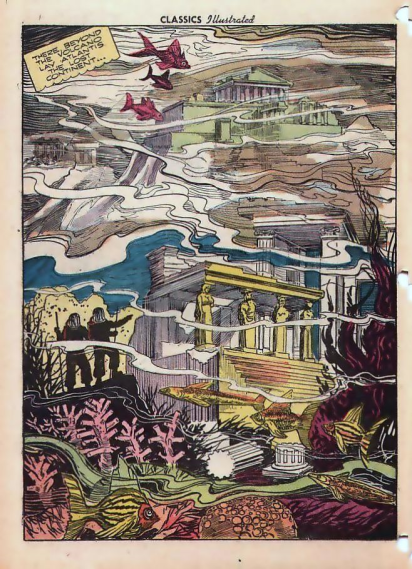

One more comic book incarnation is worth mentioning. The Classics Illustrated series published 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea as issue #47 in May 1948. It featured a single panel showing Atlantis, in particular a columned quasi-Greek temple. The issue was reprinted seventeen times through 1970.

Captain Nemo looks at the sunken Atlantis in the Classics Illustrated edition of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

The 1950s also saw the beginning of a Jules Verne revival in the movies. Disney made its version of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea . It featured many of the incidents in the novel, but, unlike the Classics Illustrated version, did not include the discovery of Atlantis. Neither had the 1916 silent version. In fact, of all the adaptations of the story for both the movies and television, only one mentions Atlantis.

As if to make up for this, they introduced Atlantis into two movie adaptations of Verne’s works where it doesn’t properly belong. In A Journey to the Center of the Earth (1959) Frofessor Lindebroek’s party finds the marketplace from an Atlantean city underground. They clearly took their cue from Pompeii, because the architecture and the shops (not to mention the volcanically-destroyed look of the marketplace) are clearly drawn from Pompeiian buildings and wall-paintings. (As an interesting touch, Lindenbroeck is played by James Mason, who had been Nemo for the Disney adaptation of 20,000 Leagues – so he got to find Atlantis, after all).

Pat Boone, James Mason, and Arlene Dahl find Atlantis underground in A Journey to the Center of the Earth

The other was in Ray Harryhausen’s version of The Mysterious Island (1961). This movie, too, features Nemo, as the book it is based on had, and gives him an expanded role over the book. During an underwater expedition, Nemo shows his companions an un-named underwater city, with Greek-style columned buildings. Even though the story takes place in the Pacific, it’s clear that Harryhausen had Atlantis in mind when he constructed the scene.

Captain Nemo explores yet another sunken city, possibly Atlantis, in The Mysterious Island

There were other mentions of Atlantis before 1960, and many more after that. But these were the main highlights of Atlantis’ appearance in pop culture before 1960. These are the things that informed George Pal, his crew, and the viewing public before George Pal made his personal Atlantis epic.

Part II — Gerald Hargreaves and his Atalanta

Sir Gerald de la Pryme Hargreaves (1881-1972) was baptized on November 16, 1881 in the church of St. Bartholomew in Westhoughton, Lancashire, England. He was the son of Thomas Haregreaves and Constance Pearson. Today Westhoughton is part of the Metropolitan Borough of Bolton in Greater Manchester, 175 miles northwest of London. By his early thirties he had moved to Bedford in Bedfordshire, about fifty miles north of London. He entered politics as a member of the Unionist (Conservative) Party and was running for office by 1910. He lost, and was scheduled for the 1915 election. He joined the Bedfordshire Imperial Yeomanry about May 1914, before the outbreak of the First World War. By a year later he was lieutenant, and shortly after June 1915 shipped out for the Front.So he didn’t get to run in Bedford. By September of 1919 he was a Captain.

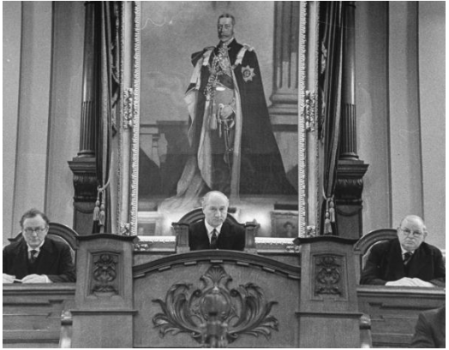

He apparently didn’t return to Bedford. We have him in Wheathampstead Hertfordshire as a judge by 1944. And later references have him serving in West London and later in London, dealing with Land issues and Divorces. He was created a Knight Bachelor at the New Year’s Honours in 1944 while a County Court Judge. He is named in correspondence with Winston Churchill, and seems to have been a staunch Conservative politician, although one source said that he “had no businesslike qualities”. We have a photo of him on the bench in 1940, balding with a fringe of white hair, looking intimidating.

Judge Hargreaves (center) on the bench. A photo from Life magazine

What’s surprising is that this soldier, officer, Conservative Politician, and Judge had an unusual hobby. He wrote musicals. He appears to have written the “book” (the prose speeches that are the bulk of the play), the music, and the lyrics. He also painted designs for the sets in watercolor.

Hargreaves wrote three musicals that I have been able to find records of. Sadly, I have no more than the names of two of these. One, registered in the United States in 1933, was The Rainbow Ring. By the mid-1950s he had registered Armada in the United States, although I don’t know when he wrote it.

But his magnum opus was clearly his play Atalanta: A Story of Atlantis—A Fantasy with Music. Several sources say that he wrote it during World War II. In 1948 it was published in a lavish edition by Hutchinson and Co. LTD. of London, with a dust jacket bearing a watercolor of the Fall of Atlantis that appears to be by Hargreaves.

There are also seven color plates with his illustrations of set designs, and 87 pages of the musical score. The entire volume is dedicated:

This book is dedicated

In lasting gratitude

To

The Right Honorable

WINSTON SPENCER CHURCHILL

P.C., O.M., C.H., F.R.S., Hon. R.A.

Whose inspiration in the hour of our greatest

Need led us from the verge of disaster to the

Pinnacle of victory and fame.

Not only did he dedicate it to Churchill, he also gave him a copy. We know, because it’s listed among Churchill’s holdings in the Archives. This was no empty or hopeful gesture – as I noted above, Hargreaves was a Conservative Party politician, like Churchill, and they corresponded.

For years I had read that George Pal based his movie on this work, which seemed hard to get hold of. No books said much, if anything about the plot. Copies in libraries seemed few and far between. Even the authoritative Encyclopedia of Fantasy had little to say about it. Internet sites seemed innocent of it.

When I first tried to find a copy through internet sources, it was hard to come by. But recently (I write this in March of 2017, having had a copy for several months) it became available online, and I bought a copy. Finally, the mystery was to be revealed.

The copy I obtained still had the dust jacket. It was inscribed by Hargreaves himself to a Doctor Roland Brawley, dated April 6, 1955. I can’t find anything about Dr. Brawley.

For the record, I can find nothing that says that Atalanta or any of Hargreaves’ other plays were every produced (although an ambiguous reference might suggest a radio production). Some sources actually state that Atalanta never was put on stage, although how they can be certain of that I don’t know. It would be something of a pity if none of them ever did see production – there is such an immense amount of effort and work put into them that you hate to see completely wasted. (I suspect that Hargreaves had some experience with getting plays produced, whether they were his own or not. At one point in Atalanta he has a character remark: “She [Atalanta] added something about once having had a play produced. Ever since then she’s considered that Death By A Thousand Cuts is too – barbarous.”)

In any event, here is, at long last, a synopsis and critique of the play.

To begin with, Hargreaves states in his Foreword that he bases his play on Plato’s Critias and upon Ignatius Donnelly’s book. Then he goes on to state something odd:

The legend of Atlantis, moreover, appears to have been bound up with that of the siege of Troy, and in this way: Troy was the uttermost colony of Atlantis; Homer says that Poseidon built the walls of Troy, and Poseidon, according to Plato’s legend, was the last ruler but one of Atlantis, Atlas being the last.

Except that no one but Hargreaves associates Atlantis with Troy; and Troy wasn’t “the uttermost colony of Atlantis” according to Donnely’s book, by a long shot. Saying the stories of Troy and Atlantis are linked by Poseidon is an awfully flimsy link. But it’s the basis upon which he constructed his play.

The actual occasion of the conflict [between Atlantis and the rest of the world] was not stated and in its absence it has been assumed in the following play that it was by the siege and sack of Troy that the Greek, or rather the Hellenic, nation, had incurred the enmity of Atlantis and had invited retaliation…

So this is how Hargreaves cobbled the inconsistent worlds of Plato’s Atlantis and Donnelly’s together – Atlantis DID plant colonies, but not in Greece, for some reason, but in Troy. The Atlantean war was revenge for the defeat of Troy.

One advantage of this for Hargreaves is that it provides him with a large and recognizable cast of characters – all the Greek leaders who came back from the war with Troy. And so we begin in the gardens of King Agamemnon of Argos, where we immediately run into a problem.

To start with, if this is right after the return from the Trojan War, nobody should be relaxing in Agamemnon’s gardens. His wife Clytemnestra was having an affair with Aegisthus while he was away, and Aegisthus slew Agamemnon as he came in the door. He, in turn, was killed by Agamemnon’s son Orestes, but not for another seven years. But that’s just the beginning.

-

Ulysses (Odysseus) is there with them. But, according to the Odyssey he spent the nine years after the Trojan War wandering the Mediterranean, trying to get home to Ithaca.

-

Menelaus, the tough King of Sparta, who defeats Paris in a one-on-one duel supposed to settle the war, is represented as a dandy who only wants to laze around and eat.

-

Paris, who dies at the end of the Trojan War in al accounts, is also there. Even though he’s a Trojan

-

Hercules, who departed for Olympus well before the Trojan War, complete with his lionskin pelt and his club. But for no discernible reason, he seems to be an Atlantean.

-

A character identified as “Zero” is present as well. Leaving aside for the moment his identity (although he shouldn’t be there, either, by orthodox mythology), the Greeks didn’t have a “zero”. The word is a much later coinage. But it sounds appropriately mysterious.

So let us ignore these mythologic absurdities, and look at the action of the play.

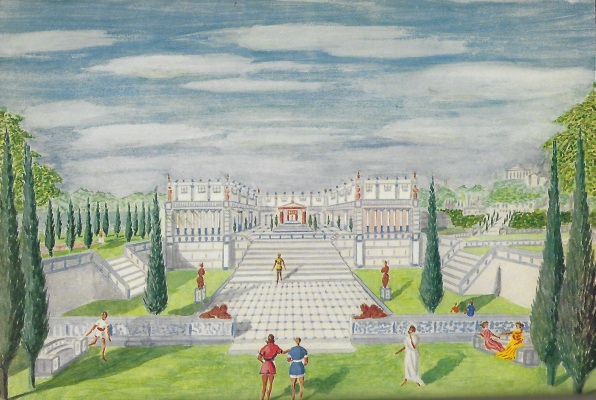

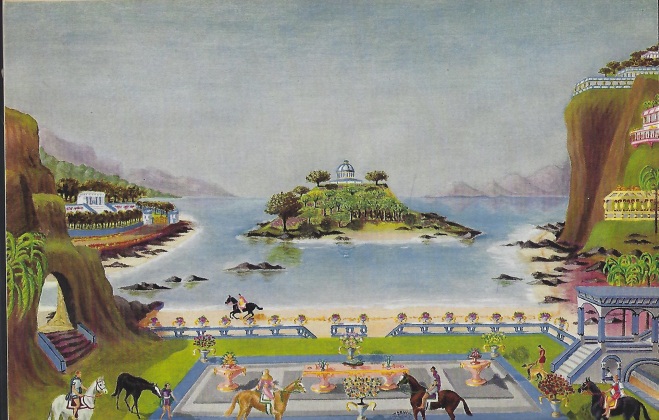

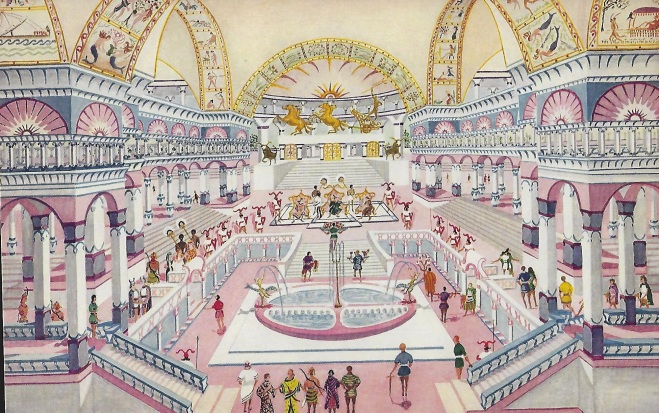

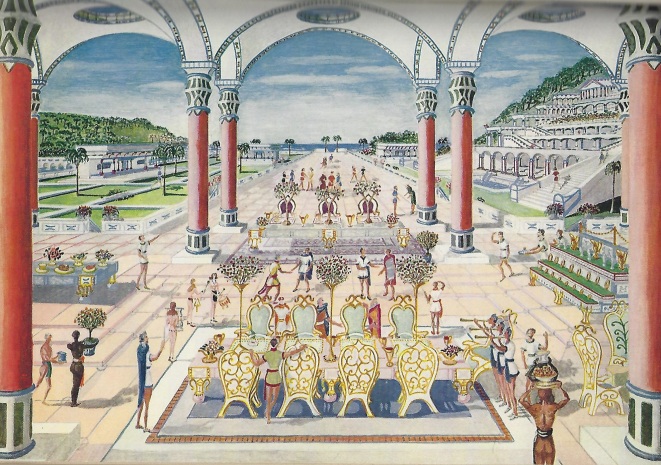

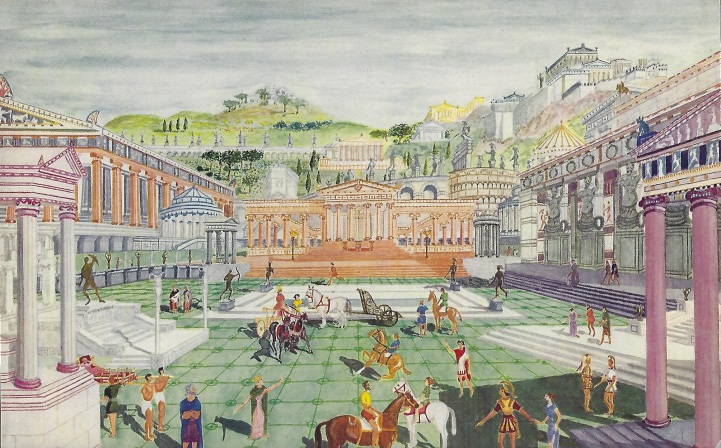

Hargreaves’ illustration for Act I, Scene I of Atalanta, representing Agamemnon’s palace at Argos. These illustrations by Hargreaves aren’t what he thought the scenes really looked like — they were meant to be visualizations of the stage scenery. All of Hargreaves’ watercolor illustrations in his published edition of Atalanta are at this scale. He clearly had grandiose ideas for the staging of his play, more in line with a major city opera house than more likely theaters.

Act I – (Agamemnon’s Garden at Argos). It’s “a few years after” the Trojan War, and Menelaus and Helen are visiting Menelaus’ brother Agamemnon. . Ulysses is there. He refers to his adventures from the Odyssey, which he’s apparently telescoped into a much shorter time. Ulysses sings a song about traveling on the sea. He and Agamemnon discuss Atlantis, which has a “peace” faction which is favored by the princess, who is called “The Atalanta”. She refuses to wed any man except the one who can beat her in a footrace. (This is pretty obviously the myth of Atalanta, except that she wasn’t from Atlantis, but Arcadia or Boeotia, and lived long before the Trojan War. But why worry about trifles?)

A fisherman named Petros comes in and tells about how ten years ago a raft was driven in by a storm near his home, with a little girl on it. A stranger leapt into the ocean, swa out, and rescued the girl, He and his wife cared for her, until two years later, when a strange ship came sailing by. She hailed it, and the sailors came by. She said they were her own people, and they took her home.

The girl left a token that she wore as a necklace, which Petros kept and eventually gave to Menelaus. He shows it to everyone, and they see that it is an unusual red metal. Ulysses examines it and declares it Auricalcum, the royal metal of Atlantis, which only the royal family wears. They realize that the girl was The Atalanta, the princess of Atlantis.

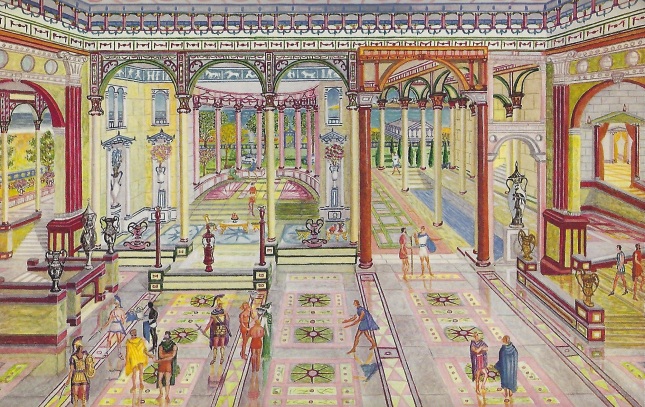

Act I. Scene II — Inside Agamemnon’s Palace at Argos

Menelaus conceives of a plan. They will send a man – the mysterios “Zero” – to Atlantis and fake a shipwreck. Zero will ingratiate himself with the Atalanta and push the case for the Peace party in Atlantis. Zero tells them that he will have no trouble recognizing Atalanta – he’s the one who rescued her on the raft

Act II – Atlantis.

Act II, Scene I — A Beach near the capitol of Atlantis

Courtiers tell Atalanta that they have discovered a dead man from a shipwreck. It turns out that he is not dead. He is Zero, who Atalanta doesn’t recognize.

Act II, Scene II — Inside Poseidon’s Temple t Atlantis. You can se a statue of him in his chariot in the center at the back.

At the Palace, we learn that King Atlas is away conquering Africa, leaving the Old King, Poseidon, who is somewhat senile, having run of the Palace, and Atalanta the de facto ruler. The War Party – who have hyphenated names derived from coastal cities – Col-Chis, Var-na, Mars-Eppa – talk about their plans, their desire to get rid of the annoying Zero (since he is advocating for Peace), and since a song about themselves as “The Super Race” (There is talk of a “Master Race”, too. The War Party seems to have a Nazi tinge). They plan to get Zero to engage in a foot race with Atalanta, which she will surely win, not only because of her speed, but because Zero limps. The punishment for losing is banishment from Atlantis. But Zero and Atalanta have fallen in love, and she “throws” the race.

Act II Scene II — The Gardens outside the Royal Palace of Atlantis

We also get a visit from the tall, white-haired Prophet Na, who is against the War Party, and talks about the earthquakes and rumblings and predicts a bad end for Atlantis. He thinks they should save their fleets for saving Atlanteans when the End comes, and not send them off to invade other countries.

The War Party persuades Hercules to challenge Zero to a fight. Zero at first refuses to take offense, until Atalanta tells him that she will not abide a coward. Zero and Hercules fight (offstage). To everyone’s surprise, Zero wins. His victory is short-lived, because Kol-chis finally recognizes Zero as the Greek hero Achilles, and accuses him of being a spy.

Zero/Achilles swears that it is not true – that he is not spying, just trying to avert war. He can’t find Atalanta’s Auricalcum pendant, which he brought to prove his identity, and is hauled off to the dungeon to await trial.

In an ominous foreshadowing, an island and a headland collapse into the sea.

Achilles is put on trial. He is found guilty, but Atalanta invokes Royal Prerogative, and decrees that his sentence should be postponed until he can teach her to beat him in a footrace. Abruptly, writing appears on the wall of the court. No one can read it, until the prophet Na arrives and declares it be a portent of coming floods (written to echo the description of Noah’s flood in Genesis).

Act II Scene IV — The Banquet Hall at the Royal Palace of Atlantis

Act III – Athens.

Act III Scene I (and only) — The Public Square at Athens

Helen argues with the poet Homer about his poem “The Iliad”. The inventor Daedalus tells Ulysses and Agamemnon about the flying chariot he is working on, but still not perfected. Icarus has evidently crashed into the sea. A Herald arrives from Atlantis, demanding the surrender of Greece. The Greeks refuse.

Mars-Eppa and others suddenly arrive and announce that Atlantis has sunk into the ocean. They throw themselves on the mercy of the Greeks.

Leander arrives and tells Daedalus that a ship has rescued Icarus from the sea. It is the Arkadia, another ship from Atlantis, captained by Na. Atalanta and Achilles are aboard. They are met by Petros, who has a glad reunion with Atalanta. Petros tells her that Achilles was the one who had rescued her.

Mars-Eppa attempts to flee in Daedalus’ flying car, but is shot down by Ulysses. Achilles and Atalanta announce their intention to wed. The Opera Ends.

Hargreaves followed this with A Synopsis for a Film Scenario, in case anyone ever wanted to turn his Opera into a film. This wasn’t exactly unprecedented – George Bernard Shaw’s published edition of his play Pygmalion included descriptions of scenes that could be filmed if his stage play were turned into a photoplay. It’s significant that, when in 1938 Anthony Asquith directed Leslie Howard as Professor Higgins and Wendy Hiller as Eliza Doolittle in his filmed version, they followed none of Shaw’s suggestions, added dialogue by five more writers, and completely changed the ending (to the one better known from the musical version, My Fair Lady). This should have been a warning that, in the unlikely case that his play did get filmed, it wouldn’t necessarily resemble what he wrote.

He suggests opening the story much earlier, with ten year old Atalanta aboard the Atlantean ship before disaster strikes, then showing the storm and destruction of the ship, her rescue, and then her growing up in the house of Petros, followed by her being found ten years later by another Atlantean ship, her reception at court, and her re-uniting with her father.

This would be followed by a glimpse of Atlantis’ conquests, as well as scenes from the Trojan War.

That’s a lot of back-material. Even if they wanted to show it all, it would probably be in the form of montages.

Then they could go into the matter of the play, but obviously ignore the explanatory scenes telling what was just seen. Much of the action from the play that occurs “offstage” can be shown in a film – “Zero” arriving at Atlantis from an apparent shipwreck, Atalanta’s footrace with “Zero”, scenes of volcanic action in Atlantis, witnessed by Na, the fight between Achilles and Hercules, the departure of the Atlantean fleet, and the destruction of Atlantis. He thought that the efforts of Daedalus and Icarus to fly might provide comic relief. And he insisted that the film end with Achilles and Atalanta arriving at Achilles’ home.

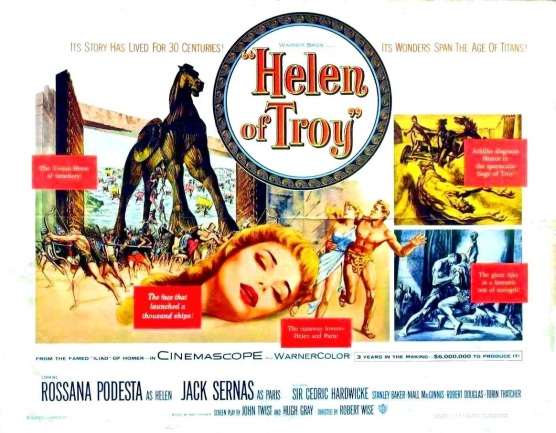

This was evidently Judge Hargreaves’ Bid for Immortality. He had this Opera turned into a book, as noted. As I also observed, he presented a copy to Churchill. He also set up a company to promote his work – Atalanta Productions, Inc., which sent it out to the motion picture studios. We know this because we have a newspaper record of a lawsuit he brought against one of them. The suit was reported by the Los Angeles Times in July of 1957. Atalanta Productions sent a copy of the book to Warner Bothers studios in April, 1953. On February 11, 1956 Warner Brothers released a film directed by Robert Wise, Helen of Troy, with a cast that included Cedric Hardwicke as King Priam of Troy, Torin Thatcher as Ulysses, Stanlet Baker as Achilles, and a young Brigette Bardot as Andraste.

The script, the work of four writers, was stated to be based on The Iliad of Homer. The suit was lodged against the authors of the script, and claimed that they made uncompensated use of Hargreaves’ script. There wouldn’t seem to be much virtue in the suit – Atlantis isn’t even mentioned in the script, most of the characters in Hargreaves do not appear in it, and those that do are in abundant material in the public domain. But it shows that Hargreaves was pushing his property, and was anxious to have it turned into a film.

One copy must have been sent to Cecil B. DeMille, the producer of extravaganzas and epics. In the early 1950s he gave his copy to George Pal, who he knew had an interest in such unusual and fantastic stories. Pal was taken by the possibilities, and tried to interest Paramount, the studio he was working for, to back production of a film about Atlantis. They refused. In the late 1950s he moved to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, making such films as tom thumb and The Time Machine, and tried to interest them in Atlantis, with no more success than with Paramount. But events were occurring that would prepare the way for Atlantis to be made into a film.

Part III – George Pal’s Atlantis

György Pál Marczincsak (1908-1981) was a Hungarian filmmmaker who specialized in dimensional animation, using wooden models with replaceable parts that were moved incrementally between frames, something he called his “Pal Doll” technique. He fled the Nazis to first Britain and then the United States, changing his name to the more Anglo-American-friendly “George Pal”. He continued to make his cartoons, now in color, and called them “Puppetoons”. They were immensely popular, and he won an honorary Academy Award for them in 1943. (They are not as well-known today because he does not have an organization preserving and perpetuating his work, but two of his films were added to the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry, and some of his animation models are in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. The Fantasy Film Worlds of George Pal (1985) and The Puppetoon Movie (1987) tried to rescue his legacy from oblivion. Sadly, his “Jasper” series of Puppetoons, featuring as its hero a young black boy, are probably doomed to the limbo of not being shown or sold due to the way Jasper is portrayed and acts.)

In the 1950s, Pal turned from producing and directing his Puppetoon shorts to making live-action films, often using his stop-motion effects. These films were often science fiction or fantasy, and many of these are regarded as classics, and are fondly remembered by fans of genre films – Rupert, Destination Moon (with a script co-authored by noted science fiction author Robert Heinlein, based on his first juvenile novel), When World Collide (based on a classic SF novel), tom thumb, The Conquest of Space, War of the Worlds and The Time Machine. Pal had a number of projects in a conceptual phase, one of which was his Atlantis film. Paramount had turned it down, and then MGM when Pal started to work for them.

That changed in 1958 with the release of the Italian fantasy epic Le fatiche di Ercole (The Labors of Hercules).

The American rights to this film (dubbed into English) were turned down by the major studios. Joseph R. Levine, founder of Embassy Pictures (which had purchased distribution rights for the Japanese film Gojira the previous year, adding scenes and releasing it as Godzilla, King of the Monsters) flew to Italy to see the film and bought the American distribution rights for $120,000. It was “One of the worst pictures I ever saw,” he said, “ But I knew it had great appeal. There was a market for anything then.” He advertised it heavily in big cities, releasing it in the US as Hercules. The film grossed $1 million in its first ten days. Levine repeated his success with the Italian-French sequel Ercole e la regina di Lidia (Hercules and the Queen of Lydia”), which was dubbed and retitled Hercules Unchained in 1960.

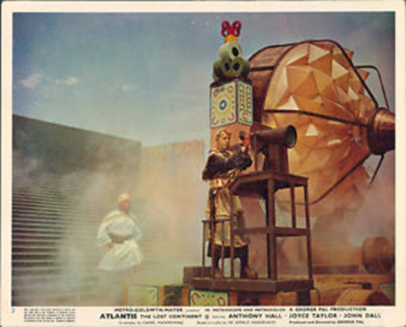

Both films were immensely profitable, which spawned a crowd of imitators. Critics called them “sword and Sandal” epics or “Peplum” films (named after the garments worn in ancient Greece). MGM decided that it wanted to get in on this action, as well, and remembered Pal’s Atlantis epic.Possibly someone recalled that Hercules was a major character in Hargreaves’ play. Pal had already purchased the rights to the play, which would have been another selling point.

But the point was to get the film made in a hurry, to cash in on a craze whose longevity was uncertain, and to keep the costs low to maximize profits. Pal could have his epic, if he made it fast and kept it cheap. It must have been agonizing for Pal, but he accepted the Faustian bargain.

Pal has been much criticized for making this film on the cheap, but I can fully sympathize, having had to produce pays with little to work with. He used whatever he could get – he re-used props from MGM’s science fiction epic Forbidden Planet, the massive quasi-Babylonian idol from the Prodigal, wardrobe from Ben-Hur and from Diane, shots from Quo Vadis anmd The Last Days of Pompeii and from Pal’s earlier film The Naked Jungle. “The only thing that motivated the choice of props and wardrobe was price,” said assistant director Reggie Callow, interviewed years later. “George would say to me, ‘Is it in stock?’ and I’d say ‘Yes’. ‘Let’s use them.’ ‘But George, it’s two thousand years time difference [between sets of props or costumes]!’ He’d say ‘Who knows?’ And that’s what we did. Anything in the picture we could steal, we stole – sets, anything.” (From Shoot the Rehearsal!: Behind the Scenes with Assistant Director Reggie Callow by Rudy Behlmer)

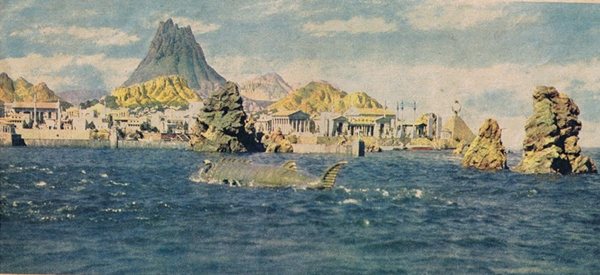

This method not only helped their financial situation, it also ultimately helped the look of the film. With props and sets that could have been designed for just about any time or place, Atlantis comes off as a truly cosmopolitan place. You can see Roman, Greek, Egyptian, Babylonian, and American motifs throughtout. Unlike most other Atlantis depictions, which favor one culture to the exclusion of others, Pal’s Atlantis actually looks as if it could have influenced all cultures.

But it wasn’t all begged, borrowed, or stolen. There was quite a bit of original special effects work, and original props built specifically for this film. And much of the work of combining elements into a shot are particularly well done, something which most citics seem to have overlooked.

Pal thought the play wasn’t really all that good, especially the musical elements. But he thought that something could be done with the basic elements. When first I obtained and read Hargreaves’ play, after all those years of wondereing about it, my first impression was that Pal had basically thrown it all out and kept only the name. Certainly the whole Trojan War aspect is gone. Only one of the characters in Pal’s film share a name with a character in Hargreaves’ Opera. The plot is vastly different. Hargreaves, although cribbing from Donelly, has no advanced technology (except for one item – Daedalus’ flying chariot), but Pal wanted to fill his story with the technological wonders of Atlantis. There are few scenes in Greece, and none involve rulers or important characters.

Upon repeated readings, however, I could see quite a few parallels between the two, although Pal overlaid the shared elements with much new material, and his script seems to have appropriated elements from other traditions about Atlantis, although it’s not obvious where they came from – possibly the Theosophists, or Cayce, or Cutcliffe-Hyne.

Pal got novelist and screenwriter Daniel Mainwaring (whose earlier genre success had been Don Seigel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers) to write an initial script (I have read of others who were said to have written an early script, but I suspect those are in error). Unfortunately, there was a Writer’s strike in Hollywood, and the script was never fully polished, which might explain some of the plot gaps and non sequiturs.

Pal also couldn’t get the actors he wanted. He originally hoped to have his hero played by Fabrizio Mioni, who had played Jason (of the Argonauts) in the original Hercules film that started the craze, but his work visa ran out, and he had to return to Italy. Pal had hired actress/singer Joyce Taylor (who had recently been in the science fiction TV series Men Into Space) as the female lead and to sing the title song. He asked her to suggest leading men. She suggested William Shatner, who had a hard time taking it seriously during the screen test, and Richard Chamberlin, but the studio chose “Anthony Hall”. His real name was Sal Ponti, and he started as a songwriter. He had recently worked for several TV series. Critics were unimpresssed with their chemistry. Taylor’s song was another casualty of the production. ( http://www.tcm.com/this-month/article/28089%7C0/Atlantis-the-Lost-Continent.html )

With all those problems and mishaps before them, Pal and company still soldiered on, doing the best that they could. It was, I think, better than it is generally given credit for, although still fallling short of what might have been. It’s easy to look at it as an example of Bad Film, fit only for a juvenile audience. Certainly it’s easy to poke fun at (and a wonderful dissection of it can be found on Elizabeth Kingsley’s website You Call Yourself a Scientist! : http://www.aycyas.com/atlantisthelostcontinent.htm ).

But I here give an account of the film, pointing out where it resembles its source material, where certain props and ideas come from, and what’s right or wrong with it. I also tell what’s been cut out.

The film opens with an animated explanation of the background of the story, straight out of Donelly. This sort of animation was a piece of cake for the former Puppetoon director, of course. But it didn’t look so much like a Puppetoon; it looked more like an educational film, or a piece of “edu-tainment” of the sort Disney put out. In fact, having it narrated by Paul Frees (one of the great voiceover talents, who had , in fact, narrated films for Disney, not to mention doing a lot of cartoon voices and dubbing in foreign films) gave it an air of respectability. So when the Voice of Frees tells you that a New World Witch riding a broom closely resembles an Old World Witch, you tend to unquestioningly accept it. The reason for all these Donnellian similarities between the Old World and the New, explains the voice, is that there was once a connection – ATLANTIS, The Lost Continent! The animated map scrolls down to reveal these words, the “A” in Atlantis written in a characteristic script, resembling a Greek Capital Delta ( Δ ) with a slight gap in it. This, the viewer would see, was a motif in Atlantean decoration, popping up everywhere. Cue the music by Russell Garcia, which sounds appropriately epic, and would be at home in any circa 1960 movie set in the ancient Classical World. (Garcia had previously scored Pal’s The Time Machine).

WE find ourselves on a Greek fishing boat, where the fisherman Petros and his son Demetrius are out fishing. They see a raft drifting near, with someone on it. Demetrius swims out to it and finds an unconscious woman there. He brings the raft to their boat and transfers her to it.

(Demetrius clearly fulfills the function of Achilles/Zero in this and, as we shall see, other functions. Petros is the only character to have made the transition from Hargreaves’ play to the film with both name and function fully intact. They decided that actor Wolfe Barzell’s voice or accent were unacceptable, so Paul Frees dubbed his voice. The result sounds a bit like Boris Badenov, who Frees also voiced.) She awakens in their dwelling, and she immediately begins complaining about it – the poor furniture, the smell of fish. She reveals that she is the princess Antillia (which recalls the Antilles, a legendary group of Islands to the West that showed up in Medieval cartography, and which was later applied to an archipelago in the Caribbean, as well as Antinea, the Queen of the Saharan Atlantis in Pierre Benoit’s l’Atlantide). She is clearly the same character as Atalanta, but shipwrecked as a woman, not a girl.

Petros takes her tantrums and insults in stride, telling her, reasonably, that she can go elsewhere if she doesn’t like their hospitality. She eventually starts trying to ingratiate herself with them, dressing up and playing to Demetrius, who starts falling for her. She makes a compass by magnetizing a needle and putting it on a float in a bowl of water (one of the examples of High Science Donnelly cites), showing how it always points the same way, but he is unimpressed.

When it is clear that they are not going to take her back to Atlantis, Antillia steals Petros’ fishing boat. Demetrius swims out to it and stops her, but she persuades him to take her out for a few days’ journey, and he will see her home. He agrees, but tells her that if they do not find it in those few days she must return with him to Greece to be his bride. She agrees.They spend several days at sea, through storms, a becalmed interlude (where, apparently just to liven things, Demetrius has a vision of a blue-skinned Poseidon rise from the sea and brandish his trident at them. As someone pointed out, Poseidon is the same shade of blue as the Morlocks in Pal’s previous film, The Time Machine. They undoubtedly had a lot of blue body makeup left over.)

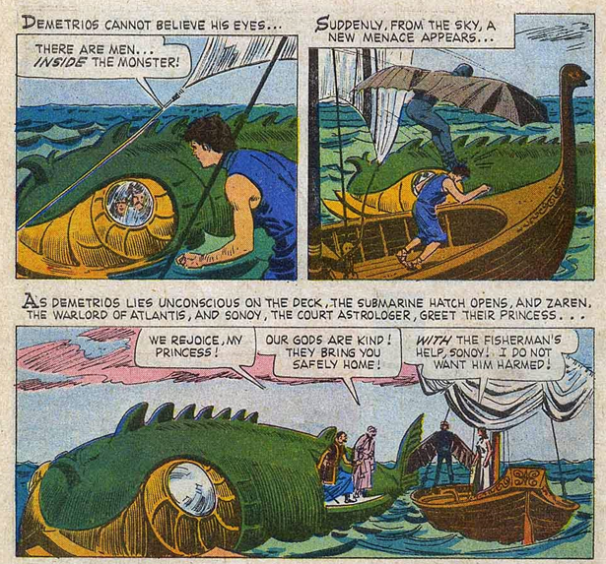

Too easily, Demetrius and Antillia fall for each other. As they are sailing along, he does not notice a strange huge fish behind them, but he can’t ignore it when it comes closer and makes loud rumbling sounds.

The huge fish dives under their boat and emerges on the other side.

Demetrius gets a fishing spar and hurls it at the thing, but, as with Ned Land trying to harpoon the Nautilus in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, the harpoon bounces harmlessly off. He prepares to do something else (as Antillia, observing his exasperation, is amused) when…

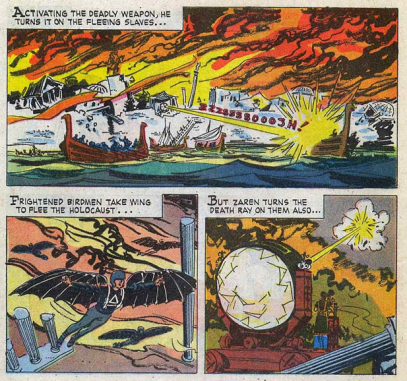

…actually, something is cut from the film at this point. We can tell what it is from the Dell comic book adaptation of the film (The film adaptations by Dell are highly variable, depending upon how much information they were given. Sometimes, as with The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad, the artist and writer were given very little information, and had to vamp it. Sometimes they were clearly give film stills to work from, as with Jack the Giant Killer. In most cases they apparently got a synopsis and a few images to use. That seems to be the case here.) Demetrius is knocked down and unconscious by a flying man, wearing a daVinci-esque set of bat-wings.

As we have observed, since the Theosophists, there was a belief that Atlanteans had some sort of flying machine, although this actually made it into few of the Atlantis stories. And the ones that did weren’t batwinged men. I suspect that Pal and Mainwaring lifted this notion from Hargreaves, who had flying devices among the Greeks rather than the Atlanteans, using the legendary inventor Daedalus as his inspiration. That, no doubt, explains why flying winged men, rather than comfortable flying galleys, appear in the film. Pal wisely switched them over to the Atlanteans, rather than the Greeks. Unfortunately, the effect, done on their shoestring budget, was terrible. Test audiences laughed at it, so all of the instances of flying men were excised from the film. The only bit that survives is a drawing affixed to the wall in Azar’s laboratory.

The “Fish” pulls up parallel to the fishing boat, and a triangular panel in the side (echoing that Atlantean “A”) swings open, revealing the Fish to be a Submarine. Out come Zaren (John Dall), Sonoy the Astrologer (Frank de Kova) and some soldiers. They welcome the Princess back, She tells them that Demetrius saved her. (She glances down at the deck, rather than sideways, which indicates that he is lying unconscious down there rather than standing at her side, a detail that I have to admit I never picked up on when I watched the film before. “Bring him aboard,” says Zaren, rather than “Bring them aboard”, another clue that they are dragging the unconscious Greek onto their submarine. And another clue that I missed. Demetrius’ being unconscious also explains why he did not protest their sinking his father’s fishing boat.

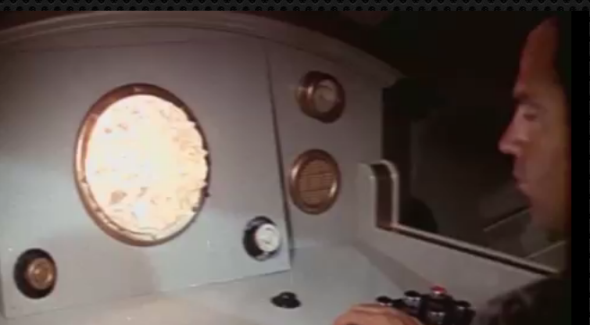

Much later, aboard the submarine, we see a control panel with a large glowing crystal in the center. As we will learn, these crystals absorb light from the sun and can release it later, and are the basis of Atlantean devices. That they have one powering a submarine recalls the solar-powered ships of Cutcliffe-Hyne’s The Lost Continent, and I again have to wonder if Pal and Mainwaring read that book for at least some inspiration.

Demetrius has been given a clean tunic to wear, and he wonders at the ship. Zaren, who’s clearly in charge, asks him if they don’t have submarines where he comes from. Zaren has a smiling, clearly false sense of bonhomie that makes you want to slap his face. The actor, John Dall, played similar characters in Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope and Kubrick’s Spartacus. This, sadly, would be his last role. Antillia comes in, and Zaren tells her they are about to surface. He sees the affection she has for Demetrius, and as he turns away you can see the sneer on his face.

The fish-shaped submarine surfaces and heads in to the port of Atlantis. This is one of the signature scenes in the film, with the weird submarine, the interesting architecture of the city, and Garcia’s score at its most epic and majestic.

The architecture is mostly Classical Greece, with plenty of columned buildings. But there’s also a stepped pyramid with an odd giant crystal atop it, and other buildings of less obvious pedigree.

The submarine docks, the Delta-shaped hatch opens, and they emerge.

Antillia gets whisked off to the Palace. Everyone else saddles up for a parade through town. In the midst of it, Demetrius is diverted down a side street and hustled off as a door closes. Zaren looks on with satisfaction.

At the Palace, Antillia and her father catch up. It seems that the King is basically ceding much power to Zaren, and when he learns of Antillia’s love for Demetrius, he replies that he’d hoped that she would marry Zaren. But Antillia has always hated him, and sees no need to change her mind now. The King suggests that she not see Demetrius for a while as he gets used to Atlantis. (Paul Frees dubbed the voice of King Cronos as well as Petros, so he did the voices of the fathers of both the leads). (Zaren seems to fill the role of all of the War Party in Hargreaves’ play, but especially Mars-Eppa, who is the leader of that faction, and who hoped to wed Atalanta. Although other members of the War Party of Atlantis are depicted in the film, they don’t get much exposure or many lines. The increasingly senile King Cronos seems to have many features of Hargreaves’ King Poseidon, but none of his funny lines. Hargreaves’ King Atlas, the real Ruler of Atlantis, who is off fighting wars, has no counterpart here.)

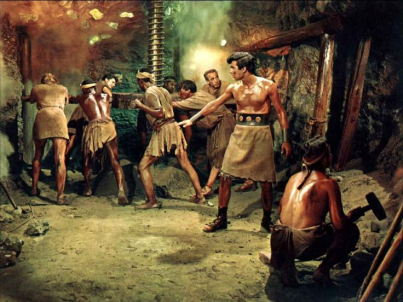

Demetrius, in the meantime, has lost his fine tunic, and is now dressed in rags with the other slaves, and with a chain attached to each ankle. The slaves are watched over by a cadre of guards dressed in the uniform of Atlantis – pointed helmet, leopard-skin shirt, leather jerkin. The next scenes, which have no counterpart in the play, are an opportunity to show us how Mean and Evil the Atlanteans are. They taunt the slaves, brandish their whips, threaten, are indifferent to their suffering and death, and do everything except laugh with a melodramatic Mwa-hah-ha! This is all to tell us why Atlantis is deserving of sinking into the ocean.

To start with, the slaves are made to cross one of those inexplicably deep canyons beloved of filmmakers. There’s a little river at the bottom to give you a sense of scale, and sheer rock walls.

The Warner Brother Coyote would feel right at home here, falling after another failed scheme to catch the road runner. Naturally, the slaves have to cross this, and without a bridge. The Atlanteans have rigged a continuous rope, rather like a ski lift, but without chairs. The slaves have to hang on to the rope and not fall. Naturally, the guy two places ahead of Demetrius does. The man immediately before him, an older guy, is in danger of doing so. Demetrius makes his way over to the older man and rescues him from falling. They get off the rope tow at the end, and the guards laugh at them. As they recover, Demetrius learns that the older slave is Xandros, from his own country. The slaves are all sailors and fishermen who were blown off course and enslaved when they landed on Atlantis.

As they walk toward the worksite they see beast-headed men off in the distance, doing simple manual labor – lifting rocks and the like. Their lowing carries over the distance to Demetrius, who exclaims “this cannot be!” and asks what caused it. Xandros says he does not know. Every now and again men are taken away in the night to the House of Fear, and when they are next seen they have the heads and minds of beasts. (I hadn’t yet heard of H.G.Wells’ The Island of Doctor Moreau, where the titular doctor transforms beats into men in his House of Pain. But every reviewer was familiar with the book and the 1932 film adaptation The Island of Lost Souls — two more film versions lay in the future.) The idea of beast-men is not in Hargreaves’ play, nor in any other Atlantis story I know of. Pal reportedly came up with it, evidently to give the Atlanteans another way to be Evil.

Demetrios and Xandros are put to work mining crystals which can store and release solar energy. “The smaller ones are used for heat and light…The larger ones..can destroy the world.” Demetrios uses a sledgehammer on a chisel that Xandros holds.

Later, Antillia is being escorted along a road on horseback. The guard sees that a line of slaves is up ahead, and goes ahead to move them off the road for the princess to pass. One of the slaves is Demetrius, who picks up a handful of the mud he has been forced into and throws it at her. “A Gift for the princes!” he shouts, before being beaten by the guards. Antillia is shocked to see that it is Demetrius.

We next see her going into a rock grotto filled with partially dressed people. It appears to be a sort of Roman Bath, much like the one in which scenes played out in the previous year’s Spartacus. She confronts her father and asks why Demetrius is a slave. Zaren, lying on a slab nearby, reminds her that it is a law of Atlantis that all castaways that land are enslaved. The king, Cronos, tells her that he himself had given the order for his enslavement. Antillia protests that Demetrius saved her life. Zaren tells her that Cronos had no choice, but that the Greek can gain his freedom through the Ordeal of Fire and Water. Antillia sees that her father has now become a puppet to Zaren, and leaves.

What’s interesting about this scene is something so understated as to be obscure, even after repeated viewings. There is an odd flickering glow behind King Cronos and the astrologer Sonoy. We never get a good look at it, and we really should, if it’s what I think it is. It has been stated, and would later be re-iterated, that the Atlanteans use their Magic Crystals for heat and light. This flickering glow looks as if it might be coming from just such a crystal, or bank of crystals, providing the heat for these Baths. If so, it’s the only time we actually see the crystals being used in their proper function – and we don’t even get a clear look at it. Indeed, even if the crystals are being used as the furnace to heat the baths, they aren’t being used for their other function, light. The scene is ostensibly lit by a battery of hanging oil lamps.

The scene at the Baths, illuminated by burning lamps. The glow in the rear, center, though, appears to be something different. It may be a Solar Crystal, but, if so, it’s the only one shown actually doing anything useful, besides the one on the submarine.

The Crystal powering the Atlantaean Submarine

Maybe the Atlanteans go in for ambiance in a big way. But a similar scene, set in the modern day, would have electric lights everywhere. This would be a good time to show the Atlanteans using their super-science – why not show it off? This is typical of the short-sightedness and missed opportunities in the film, and is probably the result of the speed at which the film was rushed through production, so we shouldn’t be too hard on Pal and his crew. I’ll have more to say about all this at the end.

Antillia goes to pray in the temple, where we see an imposing quasi-Babylonian idol with a flaming Fire Pit before it. This was one of Pal’s prize coups of appropriation. The idol is from the 1955 MGM film The Prodigal, only with the large head of the snake removed, for some reason. It looks imposing and impressive and, as I’ve said, its departure from the general Greek ambience helps to suggest that Atlantis influenced all civilizations.

Princess Atillia before the Idol. The prop is left over from the MGM movie The Prodigal

The High Priest, Azor comes in and finds Antillia praying to the idol. He takes her outside and tells her to direct her prayers to the One True God in the sky. Azor is clearly standing in to show that not Everyone in Atlantis is Evil, and some are practically Judeo-Christian (his Hat of Office is even decorated with equal-armed crosses). This lets the audience feel good about themselves.

Antillia with Azor the Priest

Azor is obviously The Prophet Na from Hargreaves’ play. Like Na, he is the tall, white-haired religious Voice of Reason, who oversees the gradual physical collapse of Atlantis that parallels its moral decay. They even got that silver hair right, with veteran actor Edward Platt playing the role as straight as possible. (Platt has been in many dramatic roles, but I can’t help seeing him in his most famous and familiar role, The Chief of the agency CONTROL in the spy spoof Get Smart. It’s not his fault, but he was just as staid and imperturbable in that role, too.)

That night there is an earthquake, causing some destruction and toppling a heavy sundial (again, you’d think that the Atlanteans, with Solar Crystal Power that can drive the propellors of submarines with regular motion would have clocks. But the sundials are at least photogenic) Demetrios is among the cleanup crew. Azor sees him and has him brought into the Temple. He assures Demetrios he is a friend, and has him wait in a room. Soon Antillia comes in. Their meeting isn’t cordial – slavery will do that to a guy – and they leave with acrimonious words.

When next we see Demetrios he is in the House of Fear, strapped unconvincingly to a board, as are other slaves, awaiting their turn with The Surgeon (who, curiously, never even gets a name; he’s played by character actor Barry Kroeger, who went on to play similar characters in the 1960s and 1970s), a man who clearly enjoys his work.

The Surgeon (Barry Kroeger) in his Evil Lab. One man is partially transformed, while Demetrios and another man, strapped to boards, wait their turn.

At the moment he is using a hand-held asymmetric crystal, which he rotates with a rhythmic thumb-flipping motion, to hypnotize the unfortunate strapped to the Board in front of him. Every now and then he forces some liquid into the man’s mouth, but the main part of the transformation seems to be hypnotic. The man already has a pair of horns, bovine ears, and a black animal nose worthy of a Carl Barks character. His heavy-lidded expression seems to indicate that he no longer cares about his metamorphosis.

Is this man being turned into a Boar, or a Bull? You decide.

The Surgeon intones “You will be a boar! Strong – Strong – STRONG!!” The music swells as his voice gets louder, then abruptly ceases. “Every day in every way you will become more and more like a boar,” he says, a line that every reviewer singles out as outrageously funny. It echoes those self-help gurus with their daily affirmations. I didn’t know about those as a kid, but I did know that Boars didn’t have horns like a bull, nor bull noses instead of snouts. Was this more fallout from the Writer’s Strike, or did they simply not notice the discrepancy? As with the oil lamps and the not-quite-seen heating crystal, this seems another case of insufficient thought and care taken by those making the film.

The now-unconscious Boar-Man, or Bull-Man, is hustled away and Demetrios put in his place. The Surgeon gloats over him, taking his little knife and scribing marks on Demetrios’ face, musing aloud what type of Beast he will become. He has a Pig brought in, apparently for shock value or for inspiration, and asks how the princess will react when she sees him as he really is. Then he says that, unlike the others, Demetrios will get to keep his mind.

Demetrios is rescued from this fate by soldiers who come to claim him for the Ordeal of Fire and Water. The Surgeon, who was despairing over the loss (“Why do they always take my best subjects?” he exclaims, to no one) perks up at this news, since it implies a swift and painful death for Demetrios. The Surgeon gloats over this, missing only a villainous “Mwa-ha-hah!” to make the caricature complete.

Demetris is taken away to the arena for the Ordeal. Sitting in the Royal Box are King Cronos, Antillia, Zaren, the High Priest Azor, and the astrologer Sonoy. The Surgeon joins them, as well. When Antillia sees that Demetrios is in the arena, she goes to stop it, but the guards cross their spears to block her way. Azor comforts her.